Table of contents

- FOLLOWING THE FLOODPATH

- Chinatown

- Southern California: An Island on the Land

- Morrow Mayo: Los Angeles

- Charles Outland: Man-Made Disaster

- The Los Angeles History Project

- Doyce Nunis: The St. Francis Dam Disaster Revisited

- Wilkman’s St. Francis Dam Documentary Film Project

- Jon Wilkman: Floodpath

- Wilkman’s Newest Book: Screening Reality

FOLLOWING THE FLOODPATH

By

JON WILKMAN

Author

Floodpath: The Deadliest Man-Made Disaster of 20th Century America and the Making of Modern Los Angeles

Bloomsbury Press, 2016

When I was in school, as with almost every kid raised and educated in the City of the Angels, the St. Francis Dam disaster didn’t exist. It certainly wasn’t in my textbooks. Why should it be? As I learned from traditional East Coast cultural arbiters, L.A. was all about the future, with no history worth knowing, a place defined by images of sunny beaches, sprawling suburbs, promotional hype, and ephemeral Hollywood fantasies.

It was only in 1978, after I returned to Los Angeles from college in the Midwest and fourteen-years as a documentarian and writer in New York City, that I rediscovered my hometown and its underappreciated history. More important for the future, shortly after settling into a house beneath the Hollywood Sign, I met my wife Nancy, a fellow writer who shared an interest in documentary storytelling.

Following the path that led us to the story of the St. Francis Dam disaster and the creation of the book, Floodpath, The Deadliest Man-Made Disaster of 20th Century America and the Making of Modern Los Angeles, is a more than a thirty-year journey through the physical, academic and literary landscapes of L.A.’s past. On the way, Nancy and I worked together on a number of L.A.-focused documentaries and co-wrote two books about the city’s past and present: Picturing Los Angeles (2006) and Los Angeles: A Pictorial Celebration (2008).

Chinatown

Even before my return to Los Angeles, as a movie buff, I was well aware of Roman Polanski and Robert Towne’s 1973 film noir, Chinatown. To many, the movie’s plotline sums up L.A. history with a single word: “water,” polluted by deceit, greed, and corruption.

Jack Nicholson/Faye Dunaway

Buried deep in the backstory of Robert Towne’s Chinatown script is a catastrophic disaster, the collapse of the Vanderlip Dam, a tragedy that haunted fictional water engineer Hollis Mulwray, and led to his murder.

It took a while, but unlike Jake Gittes, who remained baffled to the end, with the help of historians before me, some of whom were journalists and diligent non-academics, I explored the reality of what occurred near midnight on March 12, 1928, in San Francisquito Canyon, east of modern Santa Clarita. It was the beginning of a devastating floodpath that extended more than fifty-two miles west through the Santa Clara River Valley, washing away more than four hundred lives and causing millions of dollars of damage.

Mulholland and the St. Francis Dam

Although the truth behind Chinatown didn’t involve murder, it ended the career and hastened the death of a real water engineer, William Mulholland, the Irish immigrant who completed an unprecedented aqueduct in 1913, tapping the watershed of the agricultural Owens Valley in northern California, diverting it to the booming metropolis of Los Angeles, 233 miles to the south. It was a feat of shrewd politics and ambitious engineering that made America’s second-largest city possible and launched decades of often vituperative and violent debate.

Started in 1924, the construction of the St. Francis Dam was intended to create a water storage reservoir and generate hydro-electric energy. Sixty years later, when Nancy and I started our research, few had heard of the St Francis Dam and its failure, and the name Mulholland was more commonly associated with a winding road overlooking the San Fernando Valley. It wasn’t hard to convince us that this was hidden history well worth exploring, and most of all, sharing.

Southern California: An Island on the Land

The first stop on our investigative efforts was no secret to Angeleno history enthusiasts, including screenwriter Robert Towne. The book Southern California: An Island on the Land, written in 1946 by attorney, journalist, and activist Carey McWilliams, remains as insightful today as it was a year after the end of World War II. Unlike others who minimized the importance of Los Angeles, Mc Williams recognized something significant was happening in a metropolis he described as “American, but even more so.”

While acknowledging its transformative importance, like others before him, McWilliams’s treatment of the aqueduct was critical, blaming profit-driven L.A. business interests for misleading Owens Valley farmers and ranchers who had been willing to sell their water rights but didn’t realize the city’s full self-serving intentions. His mention of the St. Francis Dam was brief, blaming the failure on design inadequacies and a cover-up that added to the theme of ruthless skullduggery that infuses the plot of Chinatown.

Morrow Mayo: Los Angeles

An Island on the Land was influential, but the literary foundations for the dark side history of L.A. were laid decades earlier with the 1920s writings of California anti-aqueduct political reformist, Andrae Nordskog. Nordskog was among the first to indict the city’s water project as a scam. Following this line of thought, in 1933, Los Angeles, a book by east coast journalist, Morrow Mayo, had the widest national influence on early popular attitudes about L.A.’s illusory and noirish urban identity.

When I found a relatively rare used copy of Mayo’s angry chapter on the aqueduct story and the St. Francis Dam, I read about what he termed “[one of] the costliest, crookedest, most unscrupulous deals ever perpetrated.” He summed up with the epithet, “The Federal Government of the United States held the Owens Valley while Los Angeles raped it.”

Although the St. Francis Dam disaster is only briefly mentioned in Mayo’s jeremiad, he considered it deadly payback for William Mulholland’s “engineering folly.” While the DWP attempted to maintain a positive image the Department’s Chief Engineer and his contributions to L.A. growth and success, it wasn’t until 1963 that the causes and tragic events of March 12 and 13, 1928 received a more nuanced and in-depth historical treatment.

Charles Outland: Man-Made Disaster

In the early 1980s, I discovered Man-Made Disaster: The Story of the St. Francis Dam, written by Santa Clara River Valley rancher and dedicated local historian Charles Outland, I was astonished.

While not a trained dam engineer or degreed academic, Outland’s research was in-depth and insightful, initiated by his personal experience as a Santa Paula teenager and his acquaintances with those with other first-hand memories. Beyond this, his technical analysis revealed aspects of the collapse missed by official reports issued in the aftermath of the failure.

Published in 1963 by a Southern California press, and first revised in 1966, Man-Made Disaster received appreciative reviews, but little national recognition. Even so, by the time another updated version was released in 1977, it was essential reading for anyone interested in understanding the St. Francis Dam story. Unfortunately, despite the horrific death count and decades of mysterious obscurity, given general indifference to Los Angeles history, potential readership was limited.

Hoping the change that, Nancy and I began to think about making a nationally broadcast documentary. It would be a life and death drama and technological detective story that offers fresh context for L.A.’s emergence as a major international metropolis, with relevance to California and America’s modern environmental and political present. But there was still a lot to find out.

The Los Angeles History Project

By the mid-1980s, I had learned a lot about L.A.’s underappreciated past. That prepared me to accept an offer from PBS station KCET to produce a new documentary series, The Los Angeles History Project (LAHP), surprisingly, the first of its kind on television. The St. Francis Dam, which Nancy and I had begun to refer to as the SFD, was on the list of subjects I proposed for the project.

Doyce Nunis: The St. Francis Dam Disaster Revisited

As a result of my work on the LAHP, in 1988, I was asked to join the Board of the Historical Society of Southern California (HSSC), founded in 1883. There I got to know retired USC history professor, Doyce Nunis, the editor of the Society’s Quarterly, who it turned out, was an SFD enthusiast.

In 1995 Nunis was the driving force behind a joint HSSC and Ventura Museum of History and Art (VMHA) publication, The St. Francis Dam Revisited, which included contributions from William Mulholland’s granddaughter and biographer, Catherine, VMHA Research Librarian, and photo archivist Charles Johnson, a biographical appreciation of Charles Outland by California historian Abraham Hoffman, and a long historical and technical essay by a professor of geological engineering J. David Rogers, who has made the study of the SFD failure his lifelong work.

Wilkman’s St. Francis Dam Documentary Film Project

Informed and inspired by these new sources of expertise and support, Nancy and I intensified our research to produce a documentary film. I was especially determined to re-enact the failure with all the tools of photorealistic digital technology. I wanted viewers to be there — an expensive ambition.

The obstacles we faced were not only financial and technical. The Los Angeles Department of Water and Power (LADWP), known in 1928 as the Bureau of Water Works and Supply (BWWS), was responsible for the planning and construction of the St. Francis Dam. Not eager to commemorate a tragic failure, the agency hadn’t been very helpful when Charles Outland wrote Man-Made Disaster.

Help From LADWP

By the 1990s, LADWP’s protective grip on internal files was beginning to loosen. For me, a key figure in facilitating access to previously unavailable documents concerning the SFD was water engineer Fred Barker, the Department’s unofficial aqueduct historian. Indexes prepared by archivist Paul Soifer made searching through shelves of storage boxes easier.

LADWP Historian

Along with making our way through stacks of official documents, feeling the pressures of time, I wanted to record the memories of those who witnessed the flood and its aftermath, most of them in their seventies and eighties. To fund initial videotape interviews and the production of a short preview of the documentary, Nancy and I turned to the documentary project fund sponsored by California Humanities, commonly known as CalHum.

J. David Rogers/Norris Hundley, Jr./Donald C. Jackson

To buttress our academic credibility with CalHum, I put together a small team of advisors. Along with J. David Rogers, the group included UCLA history professor Norris Hundley, Jr. whose textbook, The Great Thirst: California and Water, a History, was well regarded, and from Pennsylvania’s Lafayette College, professor Donald C. Jackson, a specialist in the history of dams.

Of course, Hundley and Jackson knew about the SFD, but unlike Rogers, they had limited detailed knowledge. In fact, in Hundley’s eight hundred page volume, he dedicated three pages to the dam and its failure. Most of the commentary was devoted to excoriating the technical knowledge and skills of William Mulholland. Charles Outland’s book doesn’t appear in the bibliography. When Don Jackson visited the floodpath for his first detailed look, I arranged for J. David Rogers to lead an analytical tour. He described what happened, along with suggestions of why. Despite any lack of in-depth SFD expertise, I hoped Hundley and Jackson would provide much needed historical context.

Interviewing St. Francis Dam Survivors

Even before our grant proposal to California Humanities was accepted, in the late 1990s, Nancy used our own money to start to interview SFD eyewitnesses and survivors. Longtime filmmaking colleagues, cameraman Neal Brown and video editor Brian Derby helped out. We were especially interested in documenting the experiences of Latinx who experienced the disaster and were often ignored in the historical record. Researchers Vangie Griego and Nancy’s longtime friend, immigration counselor, Michelle Garcia, acted as translators when we tapped a virtually unexplored archive of local Spanish language newspapers.

Center: Mary Alice Orcutt Henderson

Bottom Row: John Nichols/Alan Pollack/Pony Horton

The “Dammies”

Even after we received our small grant from CalHum, it was necessary to squeeze work on the SFD documentary between other projects that paid the bills. As we persisted, we got to know other non-academic SFD enthusiasts, known proudly as “dammies.”

Keith Buttelman and his wife Michele, a writer for the Santa Clarita Valley Signal newspaper, were researching a book on the subject. Also from the Signal, editor Leon Worden was fascinated with the story. Independently, Frank Rock had been leading tours of the dam site. Graphic artist Pony Horton colorized archival images as he worked on a dramatic film. John Nichols was a Santa Paula photo collector who had gathered an impressive cache of SFD images, which he eventually organized into a picture book. Mary Alice Orcutt Henderson, a member of a prominent local family and president of the Santa Paula Historical Society, couldn’t help but become involved in remembering the disaster. The Santa Clarita Valley Historical Society, especially under the presidency of Alan Pollack, was an important and generous historical resource.

Catherine Mulholland

Nancy and I knew Catherine Mulholland through Southern California history circles. Although she was only five when the disaster happened and wasn’t an eyewitness, she vividly remembered visiting the site of the ruins with her father, William Mulholland’s son Perry, shortly after the collapse. As the author of her grandfather’s biography, William Mulholland and the Rise of Los Angeles, published in 1995, she was an essential name to add to our list of video eyewitness and survivor interviews.

When I finally talked with Catherine on camera in 2002, it was evident that she found an evaluation of her grandfather’s role in the SFD difficult, with many unanswered questions. Despite her understandable wish to give the man responsible for the dam the benefit of doubt, as a serious historian, she wasn’t afraid for others to honestly come to other conclusions. When our interview was over, she took me to her writing desk, with three cardboard boxes waited. They were filled with newspaper clippings she collected about the SFD during her research. “You can take these,” she said. “Just try to find the truth.” I promised to do my best.

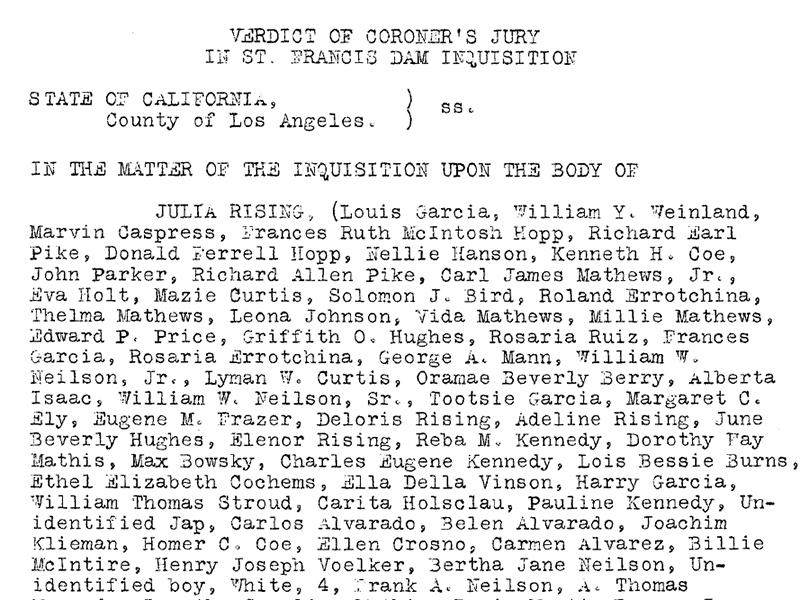

Finding the Coroner’s Inquest Report

Aside from the costs of photorealistic video graphics, the lack of one factual resource stood in the way of anyone who wanted to fully explore and tell the story of the St. Francis Disaster – the transcript of the Los Angeles County Coroner’s Inquest. From reading Man-Made Disaster, there’s evidence that Outland had a copy, but it was missing from his papers, preserved by Ventura Museum of History and Art librarian, Charles Johnson, who was another vital resource for us. All Nancy and I could find were mimeographed excerpts that included the testimony of William Mulholland, his assistant Harvey van Norman, and the final verdict. A search of the records of the LADWP, Coroner’s Office, and Superior Court, along with major archives at USC and UCLA, turned up nothing

During our frustrating search, I learned of longtime SFD dammie, Don Ray. As a journalism student in 1978, Ray knew Outland and had helped put together a fiftieth-anniversary commemoration event. He told us that he had a copy of the full Coroner’s Report, but was planning to write a book and was unwilling to share it.

We were back to square one when Nancy returned one afternoon from a day digging through the archives of the Huntington Library. After an appropriate dramatic pause, she announced, “I found it.” A full copy of the transcript was unexpectedly included in the papers of a Los Angeles civil engineer. I immediately went online and shared the good news with our advisory board and paid to make a photocopy of all eight hundred twenty pages.

J. David Rogers, who had only seen the excerpts, was especially pleased. But a short time later, Norris Hundley and Don Jackson announced that they had decided to drop out as advisers to my documentary. A few years later, I learned that they were working on a book, Heavy Ground: William Mulholland and the St. Francis Dam Disaster, which would draw deeply from the transcripts.

The Documentary Delayed

Meanwhile, other projects, including our Los Angeles focused books Picturing Los Angeles and Los Angeles: A Pictorial Celebration, a one-hour 2006 historical documentary, Chicano Rock! The Sounds of East Los Angeles; and Moguls and Movie Stars, a 2010 seven-part history of Hollywood that took three years to produce for Turner Classic Movies. Compounding this was my continued insistence on using costly computer graphics on the SFD documentary slowed progress and what Nancy and I envisioned. Then, after twenty years of staunchly holding a cancer diagnosis at bay, Nancy succumbed in 2012.

Jon Wilkman: Floodpath

Nancy’s peaceful passing got me remembering the twenty-five years we’d spent exploring the St. Francis disaster, and the file cabinets we’d filled with manuscripts and photos, and even motion picture footage. Rather than wait to finish our documentary, I decided to write a book. Bloomsbury Press agreed to publish it. My goal was to adopt a point of view that avoided past polemics without avoiding harsh realities, especially in evaluating Mulholland’s controversial role in Los Angeles history.

Although the SFD is a technological detective story, as much as possible, I wanted to tell it through first-person experiences, including those ignored in previous accounts. To go beyond Man-Made Disaster, I was able to take advantage of archival resources and computer analyses that weren’t available to Outland. These included the most detailed accounting of the death count and where the victims were buried, assembled by graduate student Ann Stansell in 2014.

Creating Floodpath was a three-year effort that was rewarded with excellent reviews and recognition as an Amazon Non-Fiction Book of the Year. Finished, I turned again to making a documentary, based on a short preview video I produced with some of our CalHum grant.

Just then, a well-known Hollywood producer optioned Floodpath for a major dramatic television mini-series. That was good news for me and a broader appreciation of the SFD story. But it meant I couldn’t pursue my documentary plans, which were considered competition to the dramatic version.

Wilkman’s Newest Book: Screening Reality

By the time the mini-series failed to sell to a network, nearly two years later, not a rare result in competitive Hollywood, I was already at work on a new book. Like Floodpath, Screening Reality: How Documentary Filmmakers Reimagined America, based on my more than fifty-year career as a documentarian, was also published by Bloomsbury Press. One of the themes of the book was how history is determined and portrayed on film, an on-going debate with connections to the polemics and forgetting that affected an understanding of the truth about the SFD.

Speaking Engagements

It would be three more years before Screening Reality reached bookstores and the distribution behemoth of Amazon in February 2020. During this time, my fascination with the SFD hadn’t diminished. I relished opportunities to do book talks at libraries, community groups, and historical societies. One of the most memorable resulted from an invitation to deliver the keynote address for the 2018 annual convention of the Association of Dam Safety Officials in Seattle. More than a thousand ADSO members attended.

As part of the program, another speaker discussed the recent Oroville Dam spillway collapse and revealed surprising connections to the St. Francis failure seventy years before — further proof that the SFD story is more relevant and important than ever. Hopefully, plans for a memorial in San Francisquito Canyon will be a significant contribution to making that more widely known. Meanwhile, for me, I’ve far from forgotten what happened on March 12, 1928, or lost my interest in producing a documentary with vivid computer graphics and personal stories that will capture what happened and why.

*****