The Heritage Junction Dispatch

A Publication of the Santa Clarita Valley Historical Society

Volume 43, Issue 1, January – February 2017

By Dr. Alan Pollack, President, SCV Historical Society

https://scvhs.org/news/dispatch43-1.pdf

Timeline of the Los Angeles Aqueduct, California Water Wars and St. Francis Dam Disaster

Historical Photos of the Disaster

Table of contents

It was in the early morning hours of May 21, 1924, and they were angry. About 3 miles north of Lone Pine, California, and just below the Alabama Gates, a group of Owens Valley protestors dynamited the Los Angeles Aqueduct. It was the opening salvo in what became known as the California Water Wars.

EATON’S VISION…AND BUILDING OF THE AQUEDUCT

History of the Los Angeles Aqueduct

Twenty years earlier, William Mulholland and Fred Eaton took a ride out to the Owens Valley in search of a new source of water for a rapidly expanding Los Angeles. Eaton, a former Los Angeles mayor, and water superintendent recognized that Los Angeles could not continue to grow if it were to depend solely on the Los Angeles River for its water supply. On this trek in 1904, he and Mulholland hatched the grandiose idea of building an aqueduct to divert the waters of the Owens River some 233 miles to Los Angeles.

To accomplish this feat, it was first necessary to obtain all the water rights to the Owens River. With the help of his friend Joseph B. Lippincott, local regional chief of the U.S. Reclamation Service, Eaton began buying up land in the Owens Valley from ranchers and farmers. He did this under the false premise that the land would be used for a federal reclamation project or for cattle ranching.

Eaton Tells His Story

At a meeting with LA city water officials on August 4, 1905, Eaton explained his enterprise: “Thirteen years ago I went to Owens Valley to study the water situation with a view to colonizing the valley, having heard a great deal about the magnificent water supply of that region.. . . .Then the idea came to me that here was the source of water supply that I knew Los Angeles would need in the course of years . . . . I caused a preliminary survey to be made then at my own expense. . . .I allowed the matter to lie dormant until the middle of last year. . . . Finally I made up my mind that the time had come for action. My idea . . . was to organize a strong company which should develop the great water power of the streams which pour down from the high Sierras and then combine with the electric feature . . . bringing the water to the San Fernando Valley . . . and from the sale of the electricity and water I was satisfied the project would be an inviting one. . . I knew the government was planning to put in irrigation works, relying on the waters of the Owen River for the supply . . . . If I had waited until after the government was at work, it would have required $1 million to $2 million more to get the water for the city, and that probably would have killed the project. . . .Later . . . I met Mr. Mathews [the city attorney], and he urged me to . . . let the water be developed by the municipality. This I disliked to do, for it would deprive me of what I believed to be a splendid opportunity to make money . . . . I finally consented . . . The result was an agreement that I would turn over to the city all the water rights I had acquired at the price I had paid for them, except that I retained the cattle which I had been compelled to take in making the deals.”

Mulholland successfully directed the completion of the Los Angeles Aqueduct in 1913. As a result, a great celebration took place in the San Fernando Valley on November 5, 1913. It was attended by some 40,000 Angelenos. Due to his technological masterpiece, Mulholland became a great hero to the city of Los Angeles. Yet the citizens of the Owens Valley considered him a villain who stole their water under false pretenses.

Increasing Tensions in the Owens Valley

Despite the hard feelings, things remained relatively quiet through the remainder of the 1910s. But the peace would not last into the 1920s. Due to continued population growth, and a major regional drought in the early 1920s, Los Angeles was forced to take actions that led to conflict with the Owens Valley citizens.

In earlier years, Los Angeles primarily took water from the lower part of the Owens Valley. Subsequently, they began buying up more land in the upper regions of the Valley to secure water rights to almost the entire Owens region. Then, as the drought worsened, the City began pumping groundwater at the expense of Inyo County ranchers. They could no longer sustain their crops and livestock due to lack of water. As a consequence, ranchers began leaving the valley in droves, causing schools in the area to close down for lack of students. Businesses faltered due to a lack of clientele.

THE CALIFORNIA WATER WARS BEGIN

Things came to a head in May of 1924. Los Angeles filed a lawsuit claiming that canal companies and individual farmers were illegally diverting water from the Aqueduct. They demanded that the farmers cease their water consumption completely.

The California water wars began at 1:00 am on May 21, 1924, when a section of the aqueduct was blown up just north of Lone Pine. Fresh tire tracks found at the site of the explosion suggested that two large touring cars had been used for the attack. Weighing at least 500 pounds, the dynamite charge was placed in a small tunnel at the base of the concrete spillway of the Alabama Gates (named for the adjacent Alabama Hills). The heavy iron gate to the spillway was damaged beyond repair. For fifty feet above and below the spillway, the concrete lining of the aqueduct was shattered. In response to the bombing, Mayor Cryer of Los Angeles offered a $10,000 reward for the capture of the perpetrators.

The next day, the Los Angeles Times reported that about forty people in ten or eleven swiftly moving automobiles with license plates removed and lights extinguished participated in the attack. They were believed to be a consortium of desert ranchers from the Mojave, and cattle owners and ranchers from the upper Owens Valley. Several letters and papers were discovered at the site of the bombing. They were thought to contain the names of men participating in the action.

According to the Times: “In the meantime, a huge force of mounted guards has been rushed from this city to the aqueduct and the entire ditch from the intake to where it crosses into Los Angeles County will be under guard day and night.”

Reginaldo F. del Valle, President of the Board of Public Service Commissioners, stated: “The attempt to dynamite and wreck the Los Angeles Aqueduct early Wednesday morning ranks as one of the most dastardly and sinister crimes ever directed against the people of this city…”

The Watterson Brothers and the California Water Wars

Investigators apparently figured out who many of the bombers were but never chose to press charges. Among the suspects in the aqueduct bombing were brothers Mark and Wilfred Watterson.

The Watterson brothers became political, social, and business heavyweights in Inyo County. They owned six bank branches in the area, with much of the money in the area held by their institutions. Intending to shut off Los Angeles’ access to the upper Owens River, the Wattersons helped form a local irrigation district to fight Los Angeles on aqueduct issues.

Ironically, an uncle of the brothers, George Watterson, was an ally of the city of Los Angeles. He helped the city obtain additional water rights for the aqueduct. For his efforts, George Watterson was branded a traitor by the Owens Valley ranchers. His life was threatened if he stayed in the Valley.

One of G. Watterson’s associates, attorney L.C. Hall, was kidnapped by an angry mob from a restaurant in Bishop on August 27, 1924. According to the LA Times, the abduction followed a series of warnings to Hall to stop investigations into the water situation in the Owens Valley on behalf of Los Angeles. During the abduction, Hall was reported to have been handcuffed, choked, and beaten.

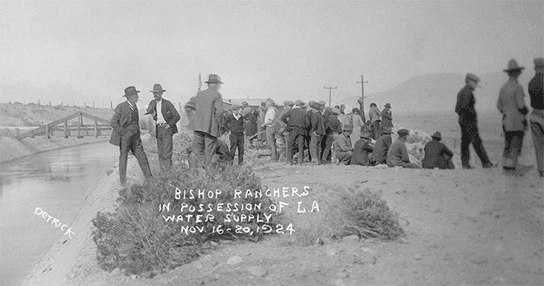

TAKEOVER OF THE ALABAMA GATES

Possibly the most infamous incident of the California water wars occurred on November 16, 1924. That morning, around seventy Owens Valley residents led by Mark and Wilfred Watterson drove south in a caravan from Bishop. They took control of the Alabama Gates spillway of the Los Angeles Aqueduct just north of Lone Pine. Then they opened the spillway gates, allowing water to flow out of the aqueduct into the surrounding valley and Owens River.

The raiders refused orders of Inyo County sheriff Collins to leave the site. They threatened to continue to waste the water, at a cost of $10,000 per day, until a committee from Los Angeles came to “settle” with them regarding their grievances with the aqueduct.

Chief Engineer of the Los Angeles water department Harvey Van Norman stated his opinion that the attack on the gates was “another gesture in a long program to force the city to buy extensive properties in the valley.”

The Growing Insurrection

Later in the day, the group of protestors grew to around 100. William Mulholland stated to the LA Times: “…It is now planned to institute damage actions against each of the men comprising the group of raiders, in addition to the injunction proceedings to be instituted in the Superior Court of Inyo County this morning. Interference with a public utility is a serious matter—of greater import than interference with mails. Mail robberies are of no more import than such an action as was taken yesterday at Lone Pine.”

The group peacefully resisted any orders to leave. They consisted of physicians, lawyers, businessmen, merchants, a Baptist minister, and even a local deputy sheriff. The minister stated “Most of my congregation is here. My place is with them.”

The seizure of the Alabama Gates was officially endorsed by a resolution of the Bishop Chamber of Commerce, a copy of which was sent to California Governor Richardson in Sacramento.

The male raiders took 24-hour shifts as they guarded the gates. Their wives and girlfriends came down from Bishop to serve food to the men. On November 19, the LA Times reported: “Inyo County is in a state of anarchy. Guerilla warfare is a possibility unless Gov. Richardson rushes state troops to the Alabama gates, where a party of ranchers and businessmen of Owens Valley have defied all efforts to dislodge them since Sunday morning, while three days’ supply of domestic water for the city of Los Angeles rushes to waste.”

Resolution of the Alabama Gates Crisis

Local authorities became concerned that peaceful resistance by unarmed men was about to escalate into an armed insurrection. Governor Richardson never had to send in his state troopers. A truce was declared on November 20 when J.A. Graves, President of the Clearinghouse Association of Los Angeles, recommended mediation of the Owens River controversy by a court of three judges selected from the courts of the State of California.

Earlier in the day, The Clearinghouse Association promised the Owens Valley protestors to use its good offices for a settlement of the controversy. The ranchers found this to be satisfactory, closed the Alabama Gates, and headed back home. But they left with continued threats of further violence against the aqueduct if their concerns were not addressed.

CALIFORNIA WATER WARS: EXPLOSIONS IN NO NAME AND COTTONWOOD CANYONS

Led by the Watterson brothers, haggling and negotiations with the city of Los Angeles continued on a tortured path throughout 1925-1927. As the California water wars continued, there were multiple instances of sabotage of the aqueduct throughout this period. These disturbances were probably perpetrated by disgruntled ranchers who were dissatisfied with negotiations with Los Angeles for payment for lands in the valley.

As the impasse between Los Angeles and the ranchers wore on, the attacks on the aqueduct become increasingly emboldened. Finally, in the early morning hours of May 27, 1927, the largest blast yet to occur did major damage to the aqueduct in No Name Canyon, some sixty miles north of Mojave.

The Bombing of No Name Canyon

According to aqueduct employees Tom Spratt, and his nephew Lew Spratt (who were witnesses to the attack), ten men surprised them in their hut. Four of the men forced them to a safe place up the canyon, while the rest of the men laid the explosives and set them off.

Harvey Van Norman later inspected the site and found 450 feet of iron pipe torn out to the tune of up to $75,000 in damage. The dynamiters, all armed and unmasked, released the Spratts shortly after the explosion and disappeared into the dark night.

Asked by the Los Angeles Times to comment on the attack, William Mulholland said he could not do so adequately without using unprintable words. Said Mulholland: “What can you say but that those blacklegs are at work up there again. We have paid them and will pay them all they have coming to them. Do they think they can get away with dynamiting from now on?”

The Bombing of Big Pine Power House No. 3

Within 24 hours, a second blast took place sixteen miles south of Bishop at the Big Pine Power House No. 3, on Big Pine Creek. It ripped apart a sixty-foot section leading into the plant.

Los Angeles was outraged and prepared to send some 600 policemen into Owens Valley. The next day, the Times editorialized: “There must and shall be no temporizing with the dynamiters who seek to enforce unreasonable demands upon the city by terrorism and sabotage. The full powers and resources of the city and of the state if necessary should be invoked to bring to swift and certain justice the criminals who have repeatedly tried to wreck the Aqueduct with high explosives placed at vital points.”

Reginaldo del Valle issued a statement calling the incident “flagrant outlawry and a vicious effort to blacken the name of Los Angeles throughout this state and nation.” He further opined that the purpose of the raid was to force the city to buy, at exorbitant prices, ranch lands in the valley, and to pay “reparations” to business interests in the communities in the valley.

The Bombing of Cottonwood Canyon

Yet another episode of the California water wars took place on June 5, 1927, at Cottonwood Canyon, twelve miles south of Lone Pine. At 1:30 am, the sidewalls of a large open concrete conduit of the aqueduct were wrecked by dynamite. The daring act took place very close to where aqueduct employees were living next to the Cottonwood Power House. Yet there were no witnesses to the sabotage. Homes of the employees were shaken but not damaged, and no injuries were reported. The same men involved in the No Name Canyon bombing were suspected in this attack, but no arrests were ever made.

In response to the repeated bombings, the water department hired 200 guards armed with Thompson machine guns to provide 24-hour protection for the aqueduct.

DOWNFALL OF THE WATTERSONS AND THE END OF THE CALIFORNIA WATER WARS

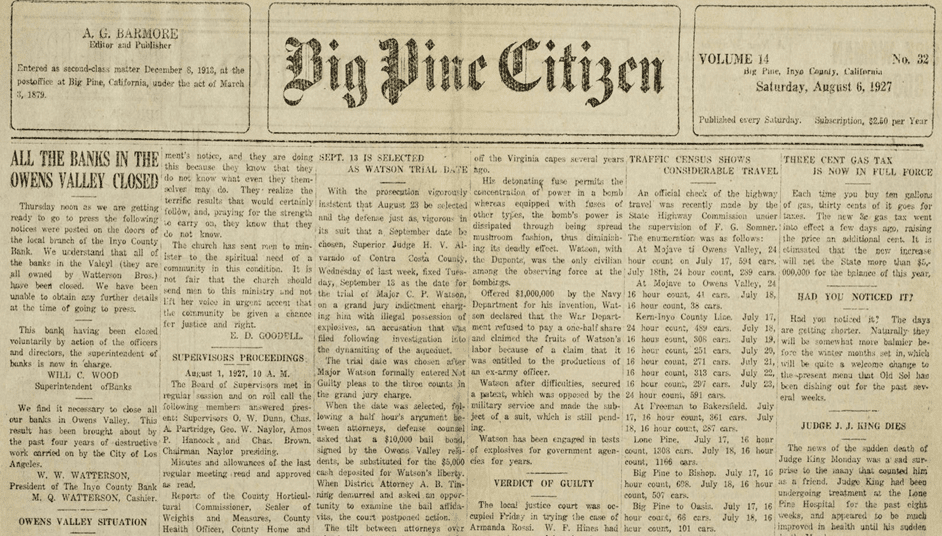

The efforts of the Owens Valley renegades in the California water wars came to an end in August 1927, when their heroes the Wattersons were exposed to have double-crossed their neighbors. Without warning, all five banks owned by the Wattersons in Inyo County closed their doors. A notice placed on the doors of each bank stated: “We find it necessary to close all of our banks in Owens Valley. This result has been brought about by the last four years of destructive work carried on by the city of Los Angeles.”

Historical Newspapers of the Disaster

Despite the Wattersons’ allegations, State Superintendent of Banks Will C. Wood, in his investigation of the banks, came to a different conclusion. He found that huge embezzlements amounting to around $800,000 were the cause of the demise of the Inyo County banks.

In spite of the continued support of their community, the Wattersons were arrested on August 13 and charged with 43 felony counts. They were released from jail on bail and traveled up and down the county proclaiming their innocence. But community support was not to last long. as the Watterson’s guilt became increasingly evident.

The Watterson brothers went on trial in November. They were found guilty on all counts and sentenced to ten years in prison at San Quentin. Because of the failure of the Inyo County banks, many residents of the valley were forced to sell their land to the City of Los Angeles and left the area. The revolt against the city’s aqueduct ended with a whimper. It could be said that Los Angeles won this battle of the California water wars, but within three months they would lose the war with an epic tragedy in San Francisquito Canyon.

Estimated reading time: 15 minutes