For more extensive information on the dam disaster, visit the archives of the Santa Clarita Valley Historical Society here:

https://scvhistory.com/scvhistory/stfrancis.htm

Table of contents

- St. Francis Dam Disaster: Victims and Heroes.By Alan Pollack, M.D. | Heritage Junction Dispatch, March-April 2008

- St. Francis Dam: Too Big Not to FailBy Alan Pollack, M.D. | Heritage Junction Dispatch, March-April 2010

- THE NIGHT OF THE FLOOD:The Failure of the Saint Francis DamBy Paul H. RippensLos Angeles Corral of Westerners: The Branding Iron, No. 212 | Summer 1998.

From scvhistory.com:

St. Francis Dam Disaster: Victims and Heroes.

By Alan Pollack, M.D. | Heritage Junction Dispatch, March-April 2008

Ace Hopewell

Shortly before midnight on March 12, 1928, carpenter Ace Hopewell was riding his motorcycle up San Francisquito Canyon road on his way to Powerhouse No. 1 of the Los Angeles Bureau of Power and Light. Hopewell passed by the mighty St. Francis Dam, which was completed just two years earlier by Los Angeles Water Chief William Mulholland. It had just been filled to capacity five days prior.

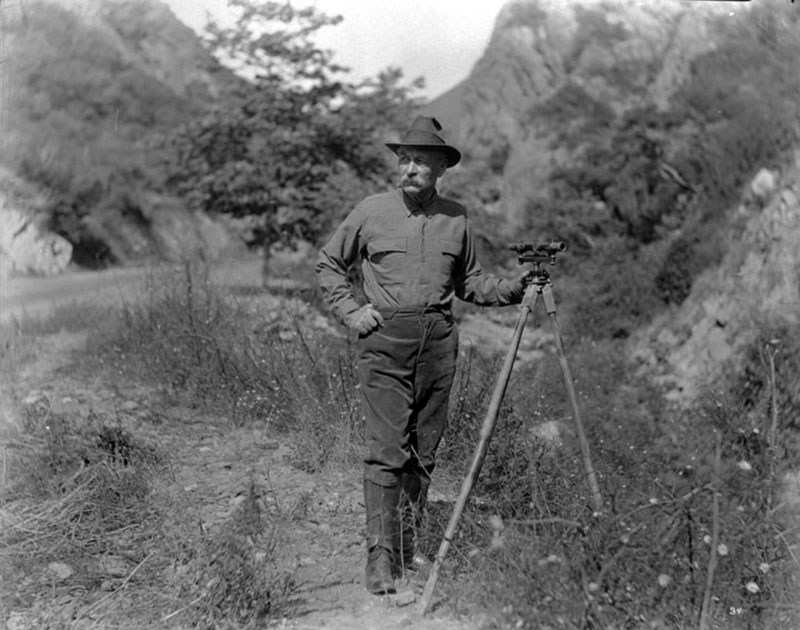

Mulholland achieved heroic status in Los Angeles when he completed the Owens Valley-Los Angeles Aqueduct in November 1913. This miraculous accomplishment allowed a small, semi-desert town to grow into the metropolis we know today.

Following the completion of the aqueduct, Mulholland directed the construction of a series of dams in the Los Angeles area. His goal was to provide a large reserve of water for the city in the event of a disruption of the aqueduct from events such as earthquakes or sabotage by angry residents of the Owens Valley. They were blowing up sections of the aqueduct to protest how Los Angeles took water from their valley.

As he rode one mile past the dam, Hopewell suddenly stopped when he heard a landslide-like crashing sound from back in the dam area. It was 11:57:30 p.m. He continued up the canyon to the powerhouse where he learned that the huge dam had ruptured, spilling 12 billion gallons and a 180-foot high wall of water into San Francisquito Canyon.

As it turns out, Hopewell was the last living person to see the St. Francis Dam before it ruptured, creating the second-largest disaster in California history. An epic flood of water and debris traveled 55 miles through San Francisquito Canyon and the Santa Clara River Valley. As a result, the towns of Piru, Fillmore, and Santa Paula were devastated. Over 400 people were killed before the floodwaters emptied into the Pacific Ocean at Montalvo between Oxnard and Ventura.

Tony Harnischfeger

At the base of the dam that night as Hopewell passed by may have been dam keeper Tony Harnischfeger and his girlfriend, Leona Johnson.

Earlier that day, Harnischfeger placed a frantic call to Mulholland when he noticed muddy water leaking from the Western abutment of the dam. While it was normal for dams to leak to some extent, the mud indicated to Harnischfeger that the base of the dam might be eroding and subject to catastrophe.

Mulholland arrived around 10:30 a.m. with his assistant Chief Harvey Van Norman and inspected the dam. He concluded that the leakage appeared normal and went back to Los Angeles — a decision he would regret for the rest of his life.

Later that night, Harnischfeger may have noticed more frightening problems with the dam. He might have been inspecting the dam base as Hopewell passed by. We will never know for sure. After the dam rupture, his girlfriend’s lifeless body was found at the base of the dam; Harnischfeger’s body and that of his son Coder were never found.

The Curtis Family

A mile and a half downstream from the dam was a group of homes for workers at Powerhouse No. 2. Lillian Curtis and her family were awakened by the roar of the floodwaters bearing down on the powerhouse. Lillian and her son scrambled up a hillside while her husband went to retrieve their daughters. The mother and son were the family’s only survivors.

Ray Rising

Ray Rising, a utility man from the powerhouse, also was awakened and faced a 10-story-high wall of water. He was swept into the flood but managed to climb onto a floating rooftop which took him to safety. He was the only other survivor at this powerhouse. The building itself was swept away by the flood, leaving only the floor slab.

Harry Carey Ranch

At the base of San Francisquito Canyon (today the Tesoro Del Valle development) was the ranch of movie star Harry Carey. The flood roared through and destroyed part of the ranch, including a Navajo Trading Post which had been a popular tourist attraction.

Carey was away on business in New York at the time. According to legend, a group of Navajo Indians, hired by Carey to run the trading post and ranch, called Carey on the night before the dam break asking permission to leave the ranch for Arizona. Their medicine man had a premonition of an impending dam rupture. But according to Carey’s son, Harry Carey Jr., the Indians actually asked Carey one month before the dam break for permission to leave — after the medicine man went deer hunting near the dam and noticed a big crack in its face.

Raymond Starbard

As the flood approached Castaic Junction, Raymond Starbard, an assistant Edison patrolman at the Saugus Substation (which can still be seen on Magic Mountain Parkway), was almost washed away by the flood. He hitched a ride to Wood’s Garage next to the Saugus Cafe. There, Starbard made a call to the Newhall Sheriff’s Substation No. 6. He was thus credited as the first person to sound the alarm about the flood.

Starbard lived in a home next to the substation built by the Edison company for its workers. His home can be seen today as one of the historic structures at Heritage Junction Historic Park in Newhall.

Ed Locke and Edison Kemp Camp

Just past the Ventura County line along the Santa Clara River was a railroad siding called Kemp. There, a group of 150 workers for the Edison company was fast asleep in a tent camp used while they were building a transmission line. Nightwatchman Ed Locke watched in horror as the huge flood of water approached the camp. He ran through the camp, waking up as many people as possible.

Locke, a true hero of the disaster, perished that night, along with 84 of the workers as the flood smashed into a geologic outcropping called Blue Cut. As a result, a whirlpool effect was created and all the tents were uprooted. Most of the survivors had their tents buttoned up. This allowed them to float on the whirlpool.

Louise Gipe

There were other heroes to recognize at Santa Paula. Louise Gipe, a night telephone operator at Santa Paula, received a call from the Pacific Long Distance telephone operator at 1:30 a.m., warning of the flood headed her way. Ignoring the peril to her own life, she stayed at her post, notifying California Highway Patrolman Thornton Edwards and calling residents in the low-lying areas of Santa Paula to warn them about the impending flood.

Thornton Edwards

Edwards would become known as the “Paul Revere of the St. Francis Dam Disaster” as he raced wildly from door to door warning residents of Santa Paula. While Edwards and officer Stanley Baker spread the alarm through Santa Paula, deputy sheriff Eddie Hearne raced up the Santa Clara River Valley toward the flood with his siren blaring to warn residents.

Hearne made it as far as Fillmore, where he met the floodwaters and had to stop his wild ride.

Alan Pollack, M.D., is president of the Santa Clarita Valley Historical Society.

From scvhistory.com:

St. Francis Dam: Too Big Not to Fail

By Alan Pollack, M.D. | Heritage Junction Dispatch, March-April 2010

Just before midnight on the evening of March 12, 1928, William Mulholland’s majestic St. Francis Dam suffered a massive collapse. As a result of the St. Francis Dam disaster, a wall of water traveled some 55 miles to the Pacific Ocean and killed over 400 people in the second-worst disaster in California history after the San Francisco earthquake and fire 22 years earlier.

But why did the St. Francis Dam fail? The headline in the Los Angeles Times of March 17, 1928, declared: “FOUR INQUIRIES UNDER WAY IN VALLEY DAM DISASTER.” In the immediate aftermath of the St. Francis Dam disaster, up to eight agencies began inquiries into the cause of the disaster, including federal, state, county, and city governments. The most significant was the 2-week coroner’s inquest led by ambitious Los Angeles District Attorney Asa Keyes.

Asa Keyes and the Coroner’s Jury

Initial theories abounded as to potential causes of the St. Francis Dam disaster, including earthquake, dynamite blasts by road workers, sabotage by the angry residents of the Owens Valley — who felt their water had been stolen by the City of Los Angeles with the completion of the Los Angeles Aqueduct in 1913 — and inappropriate mixtures of sand and gravel aggregates with the cement used for the dam. District Attorney Keyes was intent on pinning the blame for the disaster on Mulholland.

Keyes and the coroner’s jury relentlessly questioned Mulholland about the composition of the concrete, the selection of the dam site on an earthquake fault, the construction and drainage of the foundation of the dam, the anchoring of the dam to the walls of the canyon, and Mulholland’s unquestioned role in supervising the dam construction. He accused Mulholland of ignoring leaks in the dam in the days before the dam failure.

When asked by Keyes if he would build the dam on the same spot again, Mulholland replied, “No, I must be frank and say that now I would not.” Keyes pressed on, asking Mulholland why not. The reply: “It failed, that’s why. There is a hoodoo on it. … It is vulnerable against human aggression, and I would not build it there.” Mulholland himself suspected the dam had been dynamited by an Owens Valley conspiracy ring to avenge the building of the aqueduct.

Toward the end of his testimony, Mulholland humbly stated, “Don’t blame anybody else, you just fasten it on me. If there is an error of human judgment, I was the human.”

Conclusions of The Coroner’s Inquest

At the conclusion of the inquest into the St. Francis Dam disaster, the coroner’s jury stated: “The destruction of this dam was caused by the failure of the rock formations upon which it was built, and not by any error in the design of the dam itself or defect in the materials on which the dam was constructed.”

Although jurors expressed ambivalence about the inciting event leading to the disaster, they felt the preponderance of evidence favored an initial failure on the western abutment of the dam. This abutment was anchored to a rock called red Sespe conglomerate. During the inquest, Keyes demonstrated how this rock disintegrates when exposed to water.

Jurors placed the blame squarely on the shoulders of William Mulholland and his Bureau of Water Works and Supply. They further attacked the sole reliance on Mulholland’s expertise in building the dam. The final jury statement made national headlines: “The construction of a municipal dam should never be left to the sole judgment of one man, no matter how eminent.”

J. David Rogers

The St. Francis Dam Disaster Revisited

Sixty-four years later, Dr. J. David Rogers, Chair of Geological Engineering at the University of Missouri-Rolla, came to a different conclusion about Mulholland’s culpability after Rogers used modern techniques to study the failure of the dam.

In papers published in 1992 and 1995, Rogers determined the dam’s collapse actually started on the eastern abutment where the dam — unbeknownst to Mulholland and his engineers — was anchored to an ancient Paleolithic landslide made up of a rock called Pelona schist. As the dam was filled up between 1926 and 1928, this unstable hillside became saturated with water, causing a massive landslide on the evening of March 12, 1928. The collapse occurred just five days after the dam was filled for the first time to near capacity on March 7.

Causes of the Collapse According to Rogers

Rogers also noted the failure to widen the base of the dam when its height was twice raised by 10 feet (to a total height of 205 feet) to increase reservoir storage capacity. He showed that due to various deficiencies in the construction of the base of the dam, the structure, during the collapse, actually was lifted by the force of the water and tilted downstream in a phenomenon called “hydraulic uplift.”

Rogers noted that the famous center section of the dam, which remained standing, was the only portion of the dam built correctly with 10 uplift relief walls at the base. The landslide caused the entire eastern part of the dam to collapse first. As a result, large blocks of the shattered portion of the dam were carried across the downstream face of the main dam. The center section of the dam was then undercut, causing it to tilt and rotate toward the western abutment. This resulted in the collapse of the western portion of the dam as the epic floodwaters raced down San Francisquito Canyon wreaking untold havoc and destruction.

Both the coroner’s jury in 1928 and Charles Outland in has landmark 1963 book, “Man-Made Disaster, The Story of St. Francis Dam,” concluded the blame for the St. Francis Dam disaster primarily rested with William Mulholland.

Rogers, while criticizing Mulholland for not using outside consultants and for dangerously raising the dam’s height, did not find him at personal fault for the failure. Rogers stated: “Mulholland and his Bureau’s engineers belonged to a civil engineering community that did not completely appreciate or understand the concepts of effective stress and uplift, precepts just then beginning to gain recognition and acceptance.”

To Rogers, the fault lay not with Mulholland but with the lack of knowledge in his profession at the time regarding proper dam construction.

Privilege and Responsibility

Yet the plot thickens. In 2004, Donald C. Jackson, Associate Professor of History at Lafayette College, Easton, Penn., and Norris Hundley Jr., Professor of American History at the University of California, Los Angeles, published an article in the California History journal titled, “Privilege and Responsibility: William Mulholland and the St. Francis Dam Disaster.” In the article, the blame shifts back to Mulholland.

Jackson and Hundley point out that while Mulholland correctly placed drainage wells at the base of the center section of the dam, he chose to forgo this and other necessary procedures in the outer parts of the dam, ignoring the possibility of the uplift phenomenon in those sections as water seeped into the adjacent hillsides.

What Mulholland Should Have Known

The authors further point out that before 1910, little attention was paid to hydraulic uplift in dam building. However, concerns about the phenomenon were expressed in the late 1800s and intensified with the collapse of a concrete gravity dam in Austin, Penn., on Sept. 30, 1911. As a consequence of this dam rupture, 78 lives were lost. The collapse of this dam was blamed on hydraulic uplift.

Keeping this tragedy in mind, throughout the 1910s and early 1920s, several concrete curved-gravity dams across the country — all before the St. Francis — were built to protect against the uplift problem. They used extensive grouting, placement of a drainage system along the length of the dam, and a deep cut-off trench.

At least three technical books published in the 1910s pointed out the dangers of uplift and how to compensate for it. Jackson and Hundley further claim: “By 1916-1917, serious concern about uplift on the part of American dam engineers was neither obscure nor unusual. Equally to the point, in the early 1920s, Mulholland’s placement of drainage wells only in the center section of St. Francis Dam did not reflect standard practice in California for large concrete gravity dams.”

Conclusion of Jackson and Hundley

The authors come to the conclusion: “Despite equivocations, denial of dangers that he knew — or reasonably should have known — existed, pretense to scientific knowledge regarding gravity dam technology that he possessed neither through experience nor education, and invocations of ‘hoodoos,’ William Mulholland understood the great privilege that had been afforded him to build the St. Francis Dam where and how he chose. Because of this privilege — and the decisions that he made — William Mulholland bears responsibility for the St. Francis Dam disaster.”

Historical Photos of the Disaster

Alan Pollack, M.D., is president of the Santa Clarita Valley Historical Society.

From scvhistory.com:

THE NIGHT OF THE FLOOD:

The Failure of the Saint Francis Dam

By Paul H. Rippens

Los Angeles Corral of Westerners: The Branding Iron, No. 212 | Summer 1998.

The night of March 12, 1928, was still; the residents of the Santa Clara River Valley northwest of Los Angeles relaxed following another beautiful spring day. Rains had graced the region in previous days but this day had been dry with scattered clouds.

To the north of the town of Saugus, in San Francisquito Canyon, a disaster of epic proportions was about to occur. One that would claim over 450 lives, second only to the great San Francisco earthquake of 1906. The Saint Francis Dam, part of the Los Angeles Aqueduct system that supplies water for Los Angeles, was about to fail.

Mulholland Inspects the St. Francis Dam

Rumors had spread in the canyons below the dam that the structure was unsafe and that it had several major leaks. This concern was also in the mind of dam keeper Tony Harnischfeger when he called Los Angeles on the morning of March 12 to advise William Mulholland, chief engineer of the city’s water department, that another leak had occurred.

Mulholland and his assistant Harvey Van Norman made the two hour trip to the dam and, following an inspection, proclaimed the dam to be perfectly safe. However, there were forces no one suspected that would cause the dam to collapse, releasing over 12 billion gallons of water on a destructive rampage through the canyons and valleys of Los Angeles and Ventura County.

At 11:57:30 P.M., the dam could no longer hold back the tremendous pressure of the water and, as the east abutment began to fail, the water started its course toward the Pacific Ocean, 53.8 miles distant.

Events Leading to the St. Francis Dam Disaster

The events leading to the disaster began in 1900. Los Angeles was growing faster than anyone had imagined. The City of Angels was now home to 100,000 people, and water was becoming a major issue. The city could not continue to grow with the water being provided by the Los Angeles River.

Fred Eaton, an engineer and former mayor (1898-1900), had explored the possibility of building an aqueduct from Owens Valley, some 250 miles north of Los Angeles. He persuaded William Mulholland to consider this water source for the city.

In July 1905, the voters of Los Angeles approved a $1,500,000 bond issue to acquire Owens Valley lands and water rights. An additional bond issue of $23,000,000 was passed in 1907 to construct what would become one of the engineering marvels of its time.

Construction of the Los Angeles Aqueduct

Construction of the aqueduct began in 1908 and was completed in 1913, on time and under budget, an unheard-of thing today. On November 5, 1913, some 40,000 Angelenos turned out to watch the Owens River water cascade into a San Fernando reservoir, later to be called the Van Norman Reservoir. “There it is,” said Mulholland, “take it.”

According to some officials, with the aqueduct the city had all the water it would ever need. The city constructed two power plants in San Francisquito Canyon with Power House No. 1 regulating the water coming into Los Angeles.

The Owens Valley Water Wars

Everything seemed to be perfect until certain people in the Owens Valley started to rise up against the city and its aqueduct. On May 21, 1924, a group of men dynamited the aqueduct spillway gate near Lone Pine. This would be only the first of many acts of sabotage to the city’s water system.

Following these acts, Mulholland decided to construct an additional storage facility to ensure that the city would have adequate water. Mulholland was also concerned that the Elizabeth Tunnel, which was bored through the San Andreas Fault, could fail in a seismic event.

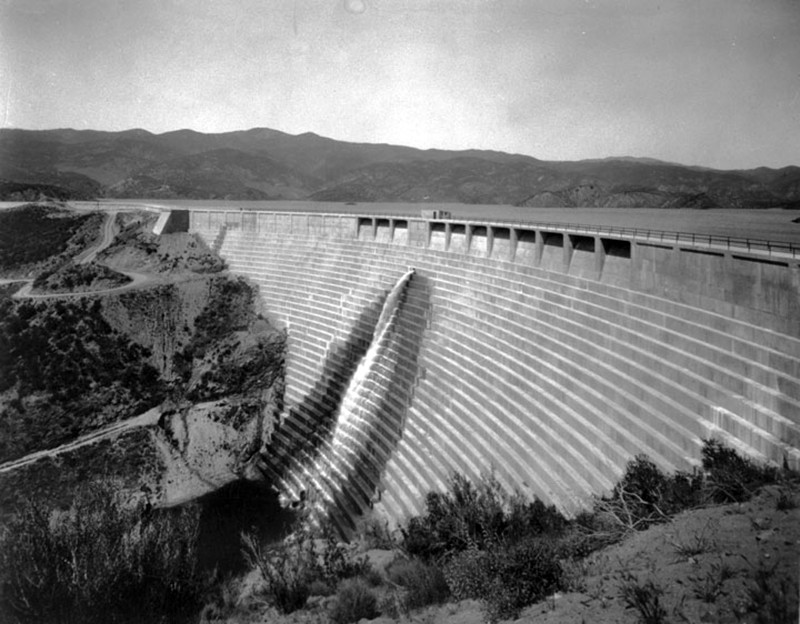

Construction of the Saint Francis Dam

He decided to construct a new reservoir that would be formed by the Saint Francis Dam, a 688-foot long arched dam with an additional 588-foot wing dike on the west side. The reservoir would cover 600 acres and have a capacity of 38,168-acre feet.

Work began on the dam in 1924 with the pouring of concrete commencing in August of that year. By 1926 the dam was completed and the reservoir began to fill.

As the water level rose behind the great dam, leaks and cracks appeared not only on the face of the dam but at the east and west abutments. The cracks in the concrete were packed with oakum to seal off the leaks. This operation was not entirely successful, for water continued to permeate through the downstream face of the dam. Workers installed a two-inch pipe to the leak on the west abutment, adjacent to the inactive San Francisquito Fault line, and the water collected and carried down to dam keeper Hamischfeger’s cottage for home use.

By April 1927, the reservoir had filled to within ten feet of the spillway, and most of May 1927 saw water elevations within three feet of the overflow. No significant change was detected in the seepage from either abutment other than what could normally be expected from the increased pressure. William Mulholland stated, “Of all the dams I have built and of all the dams I have ever seen, it was the driest dam of its size I ever saw.”

The Week Before The Collapse

The water level in the St. Francis Reservoir rose steadily until March 7, 1928, when Mulholland ordered that no more water be turned into the reservoir. The level was within three inches of the spillway and would tend to waste over the dam in case of high wave action caused by the prevailing down canyon winds. The reservoir held enough water to last the entire city for a year. Meanwhile, gossip continued by inhabitants of the canyon regarding the leaking dam and the amount of water flowing down the canyon. Whenever neighbors in the canyon stopped to talk, the subject invariable was about the dam.

One canyon dweller said:

“I stood there and talked to some friends of mine working in the rock quarry. One day we were talking about that leak increasing and I told them I said, ‘It looks like that leak is getting pretty bad,’ and they asked me if there was any danger of the dam breaking and I told them I didn’t know“.

The Day of the Saint Francis Dam Disaster

The morning of March 12 began like any other. The keeper of the dam went about his work which included checking for new leaks. His concern over a leak at the west abutment prompted the call to Mulholland and the subsequent inspection.

At Powerhouse No. 2, a short distance down canyon from the dam, the day shift was ready to start its tour at seven, while the men who had been on duty since eleven the previous night looked forward to breakfast and a late bed. Mothers readied their children for school and prepared breakfast for their men. Life was quiet and serene at the homes located close to the powerhouse.

As evening fell, families gathered to visit and to pass the time. A lone motorcyclist made his way up the canyon on his way to Powerhouse No. 1. A mile past the dam he stopped after he heard a loud noise. He listened to what he thought was the sound of a landslide, but they were common in the canyon, so he continued on his way.

The Dam Collapses

At 11:57:30 P.M. people in Los Angeles, some 50 miles away, noticed the lights flicker momentarily. Bureau of Power and Light operators noticed a sharp drop in voltage for two seconds. At the Saugus substation of the Southern California Edison Company, the transmission line to Lancaster shorted out, blowing up an oil switch in the station.

Powerhouse No. 2 Destroyed

High above Powerhouse No. 2, the surge chamber attendant was awakened by what he thought to be an earthquake, but the vibrations grew stronger. Suddenly the lights dipped to a dull glow, remained for a second or two, and then went out. He knew something was wrong at the powerhouse. The attendant was right, something was wrong at the powerhouse, for a wall of water 120 feet high had swept over the building washing away everything except the generators. Of the twenty-eight workmen and their families living at Powerhouse No. 2 only three people survived.

The flood had taken only five minutes to travel from the site of the dam to the powerhouse. There was nothing that could have stopped the rush of the water as it stripped San Francisquito Canyon bare. Buildings, cars, livestock, trees, people, and the soil itself were washed toward the ocean.

By now authorities were becoming aware of what had happened. Powerhouse No. 1 sent a man down the canyon to investigate; he reported that the dam was gone and the reservoir was empty.

Edison Company Assets Destroyed and Employees Killed

Downstream, the rampaging water continued its destructive path taking out the Edison substation in Saugus as it made its turn to the west. The wall of water, still 75 feet high, swept over the buildings of Castaic Junction and destroyed the bridge across the Santa Clara River.

At Kemp (Blue Cut), the Edison Company’s camp of workers was right in the path of the flood. The night security officer, Ed Locke, heard the rumbling vibrations of the approaching water but could not determine what the problem was until it was too late.

The flood wave struck the hills west of the camp and rebounded up the valley. Locke tried to awaken the sleeping men but his efforts were, for the most part, futile. Of the one hundred fifty men in the camp, eighty-four perished in the cold floodwaters, including the heroic watchman.

The onslaught of the flood swept across the Camulos Ranch. The water tore through the groves of orange trees, ripping them out of the·ground. It did little to slow the advance of the water as it continued toward Fillmore and Santa Paula.

Louis Gipe and Thornton Edwards: Heroes in Santa Paula

At 1:30 AM. on March 13, 1928, the night telephone operator in Santa Paula received an urgent call from the chief operator of the Pacific Long Distance Telephone Company. She told the Santa Paula operator that the St. Francis Dam on the Los Angeles Aqueduct had broken and released a tremendous wall of water that was sweeping down the Santa Clara Valley.

The Santa Paula operator immediately called Highway Patrolman Thorton Edwards to notify him of the impending disaster. Edwards quickly dressed and boarded his motorcycle to start a wild ride that would earn him the title “Paul Revere of the St. Francis Flood.” He knocked on doors to awaken people and tell them of the pending flood. Finally, he used the siren on the cycle and raced up and down the streets in the danger zone in an attempt to warn the residents.

Destruction in Fillmore and Santa Paula

The floodwaters roared past Fillmore, destroying homes in the low lying areas and taking more lives as it continued toward Santa Paula. Bridges across the Santa Clara Valley river were swept away one by one.

As the river level rose in Santa Paula, homes lining the river were floated off their foundations or splintered into pieces depending on their location. Homes became houseboats and sailed around areas of the city, one ending up four blocks from its original location.

The water continued past Saticoy and under the Montalvo bridge and finally, five and one-half hours after it began, the floodwaters, still 15 feet high and now semi-solid with mud, debris, and bodies reached the Pacific Ocean. The flood was over, and the huge clean-up began.

The Aftermath of the St. Francis Dam Disaster

The City of Los Angeles accepted the responsibility for the disaster and agreed to pay the cost of the clean-up and reconstruction. An official report stated that the City of Los Angeles expended $9,392,487.57 in rehabilitation work and the settlement of claims.

From the onset, Mulholland accepted the blame, telling the Coroner’s inquiry that he “only envied those who were killed.” His final statement at the inquest told how he felt when he said “Don’t blame anyone else, you just fasten it on me. If there was an error in human judgment, I was the human.”

Why Did the Dam Fail?

But what had caused the great dam to fail? Theories were many but recent findings take most of the blame off William Mulholland and place it on events and factors that neither he nor his engineers knew about at the time of the construction of the dam.

In “The St. Francis Dam Disaster Revisited,” J. David Rogers points out that the area of San Francisquito Canyon where the dam was constructed has many ancient mega landslides of which Mulholland was unaware. These slides contributed to the· overall failure of the structure. Rogers discusses the effects of uplift pressures on gravity dams.

He states:

“In lay terms, uplift pressures are caused by buoyancy due to simple submergence or percolation. When water fills behind a dam, the dry dead weight of the dam is significantly reduced because of the water pressures within the foundation rock beneath the dam are pushing upward“.

So the failure of the St. Francis Dam was not caused by anything that Mulholland did, but because of things he did not know. As pressures built, the great dam was lifted upward. At the same time, the east abutment area had become saturated with moisture and as the structure lifted, the mountainside on the east side slid into the reservoir creating a giant opening for the water to escape.

As the water started its rush down the canyon, the dam leaned to the east and broke apart. As the dam fell in gigantic pieces, a flood wave estimated at 1.7 million cubic feet per second began its race to the Pacific Ocean.

Today remnants of the dam remain in San Francisquito Canyon, but memories of the disaster remain only in the many books written on the subject. Unfortunately, William Mulholland died in 1935 without knowing what really happened to cause the night of the flood.

Suggested Readings

Davis, Margaret Leslie. “Rivers in the Desert: William Mulholland and the Inventing of Los Angeles.”

Hoffman, Abraham. “Vision or Villainy: Origins of the Owens Valley-Los Angeles Water Controversy.”

Kahrl, William. “Water and Power: The Conflict over Los Angeles’ Water Supply in the Owens Valley.”

Nadeau, Remi. “The Water Seekers.”

Southern California Quarterly Vol. 79, No. 3 (Fall 1997).

Outland, Charles F. “Man-Made Disaster: The Story of St. Francis Dam.”

©Paul H. Rippens | Used/archived by permission of the author.

Estimated reading time: 29 minutes