St. Francis Dam Disaster: An Extended Timeline

Compiled by Alan Pollack

SCVHistory.com | March 13, 2014

https://scvhistory.com/scvhistory/stfrancistimeline_pollack2014.htm

September 4, 1781: A group of 44 settlers known as Los Pobladores found El Pueblo de Nuestra Señora la Reina de Los Angeles del Río de Porciúncula. In the early days of the pueblo of Los Angeles, the city water supply is obtained from the Los Angeles River. Water is brought to the pueblo by way of a series of ditches, or zanjas. The main ditch is called the Zanja Madre, or mother ditch.

1868: The city of Los Angeles enters into a 30-year lease contract with the private Los Angeles City Water Co. to provide water to the city.

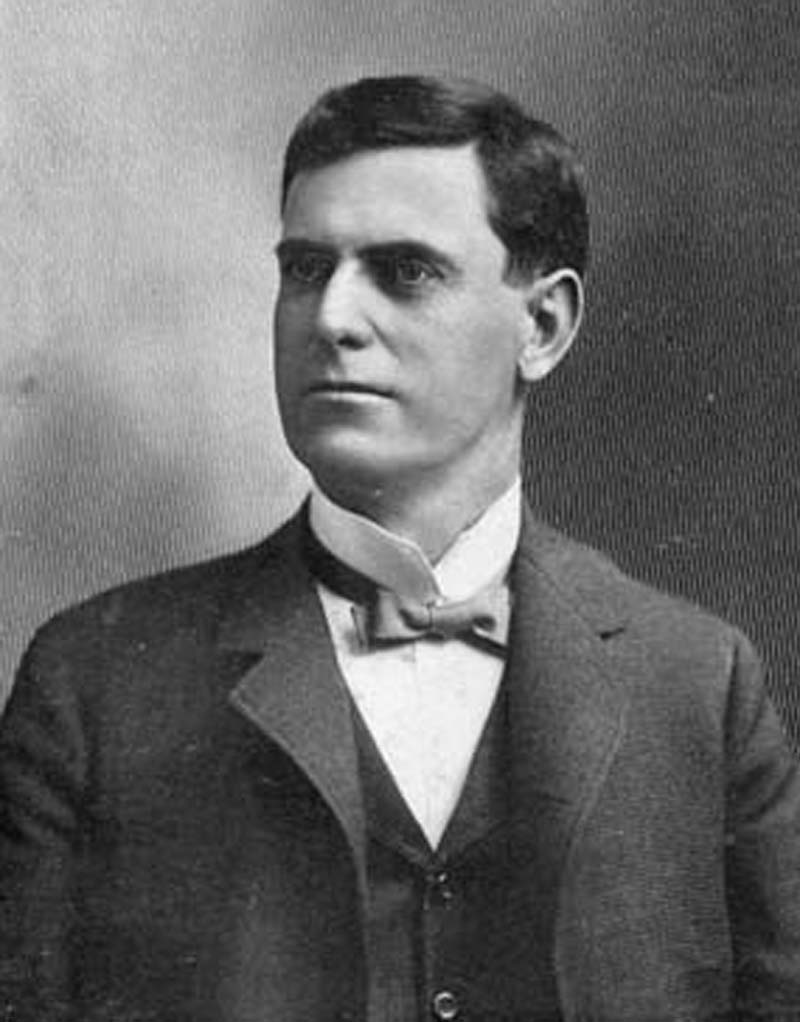

1875: Fred Eaton becomes the superintendent of the Los Angeles City Water Co. at age 19.

1877: Irish immigrant William Mulholland arrives in Los Angeles.

1878: Mulholland is hired to work for the Los Angeles City Water Co. as a zanjero (ditch tender).

1886: Mulholland becomes superintendent of the Los Angeles City Water Co. at age 31.

1893: Eaton takes an excursion into Inyo County. As a result of his journey, he visualizes an idea for water development for Los Angeles. Because the population of Los Angeles is growing rapidly, its water supply cannot be sustained by the Los Angeles River alone.

1898: Eaton becomes 24th mayor of the city of Los Angeles (1898-1900).

February 3, 1902: The city of Los Angeles formally takes ownership of the first Los Angeles municipal waterworks system. Mulholland continues as superintendent of the Los Angeles Bureau of Water Works and Supply (the future DWP).

History of the Los Angeles Aqueduct

1904: Mulholland drives on a buckboard through Newhall and Saugus with his friend, former Mayor Eaton. They were en route to exploring the Owens Valley east of the Sierra Nevada range. Eaton had previously visited the Valley in 1893. On this journey, Eaton wants to convince Mulholland that the Owens River can be diverted to Los Angeles to become the extra water source the growing city desperately needs. It is on this trip that Mulholland and Eaton hatch the idea of building an aqueduct from the Owens Valley to the San Fernando Valley.

1904: Eaton, with the help of his friend J.B. Lippincott, begins buying up land in the Owens Valley under the pretense that the land was needed for a reclamation project. Lippincott’s work as a supervising engineer for California in the newly created U.S. Reclamation Service had brought him, independently of Eaton, to the Owens Valley. In the spring of 1903, his boss, Fredrick H. Newell, had suggested the Owens Valley as a site for a potential reclamation project.

March 1905: Eaton travels to the Owens Valley to buy land options and water rights. The major acquisition during this trip is the Long Valley Reservoir site (present-day Crowley Lake). Eaton pays $450,000 for a 2-month option on ranch lands and 4,000 head of cattle. In all, he acquires the rights to more than 50 miles of riparian land, basically all parcels of any importance not controlled by the Reclamation Service.

March 22, 1905: Mulholland reports to the Board of Water Commissioners that he has surveyed all of the available water sources in Southern California. In his report, he recommends the Owens River as the only viable source. Immediately following Mulholland’s presentation, Eaton proposes that the city acquires from him whatever water rights and options he was able to secure to further the project.

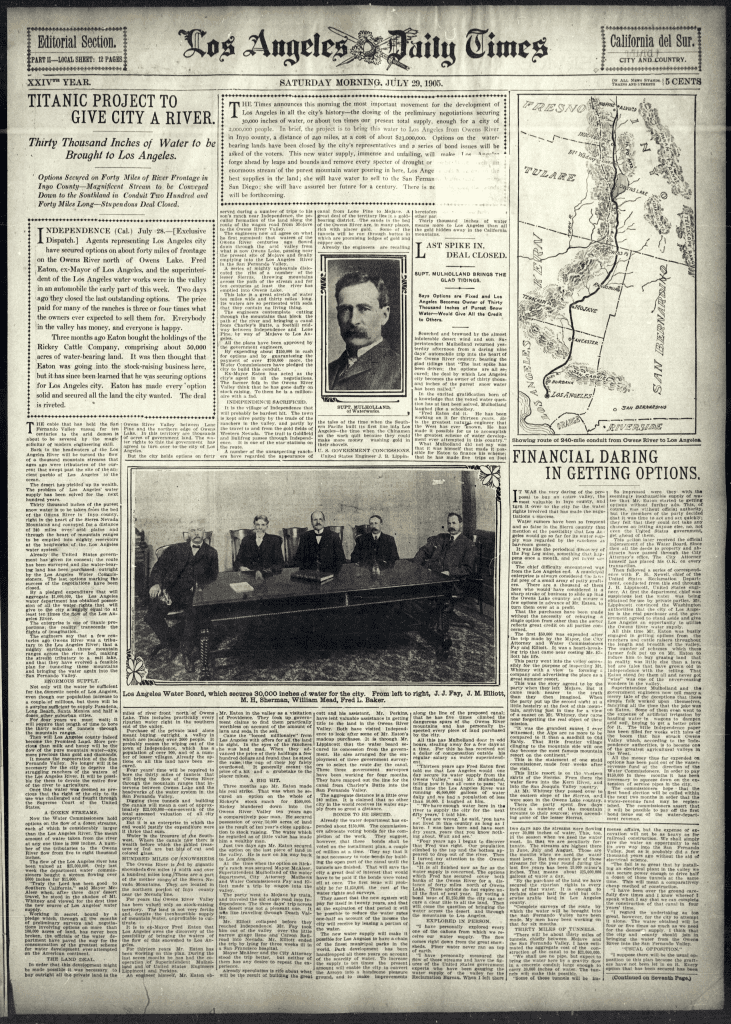

July 29, 1905: Mulholland returns from a car trip to the Owens Valley. He says: “The last spike is driven … the options are secure.” The Los Angeles Times trumpets: “TITANIC PROJECT TO GIVE CITY A RIVER.”

1905: Los Angeles voters approve a $1.5 million bond issue by more than a 10-to-1 margin. Through publicity generated both by the Los Angeles Times’ editorial stance and investigations conducted by the Chamber of Commerce, the community rallies to support the initial bond issue to purchase land and begin preliminary construction of the Los Angeles Aqueduct.

1907: Los Angeles voters again give their overwhelming consent to the project. They approve a $23 million bond issue for aqueduct construction.

1908-1913: Mulholland directs construction of the 233-mile-long Los Angeles Aqueduct from the Owens Valley to the San Fernando Valley. As a result of his efforts, the project is completed on time and within budget. Because of this, Mulholland becomes a hero to the citizenry of Los Angeles.

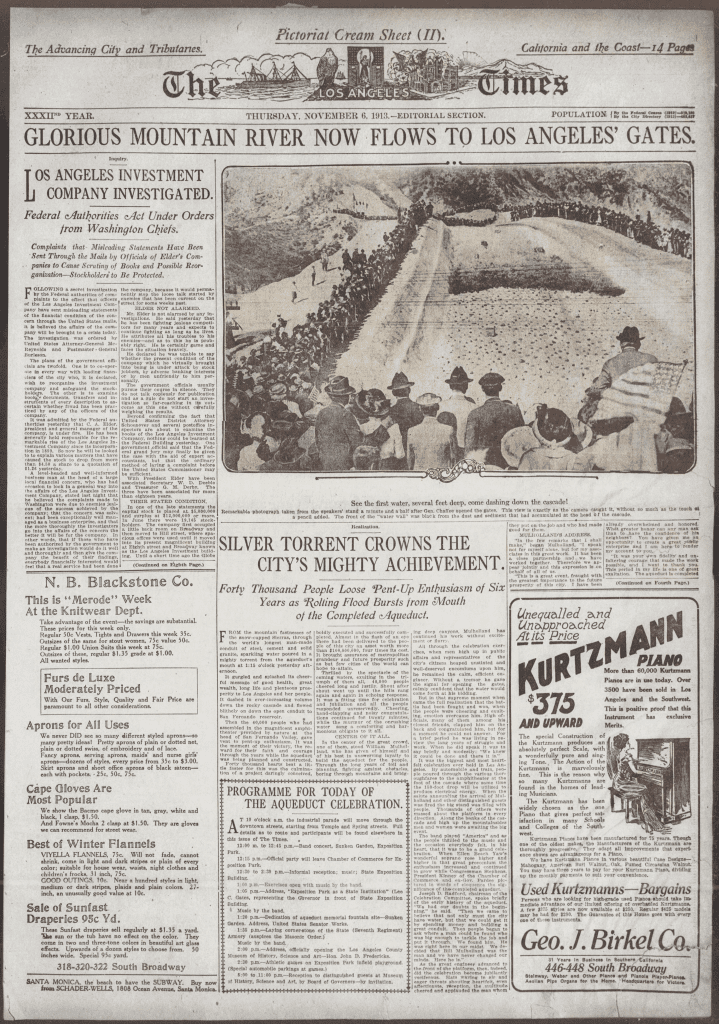

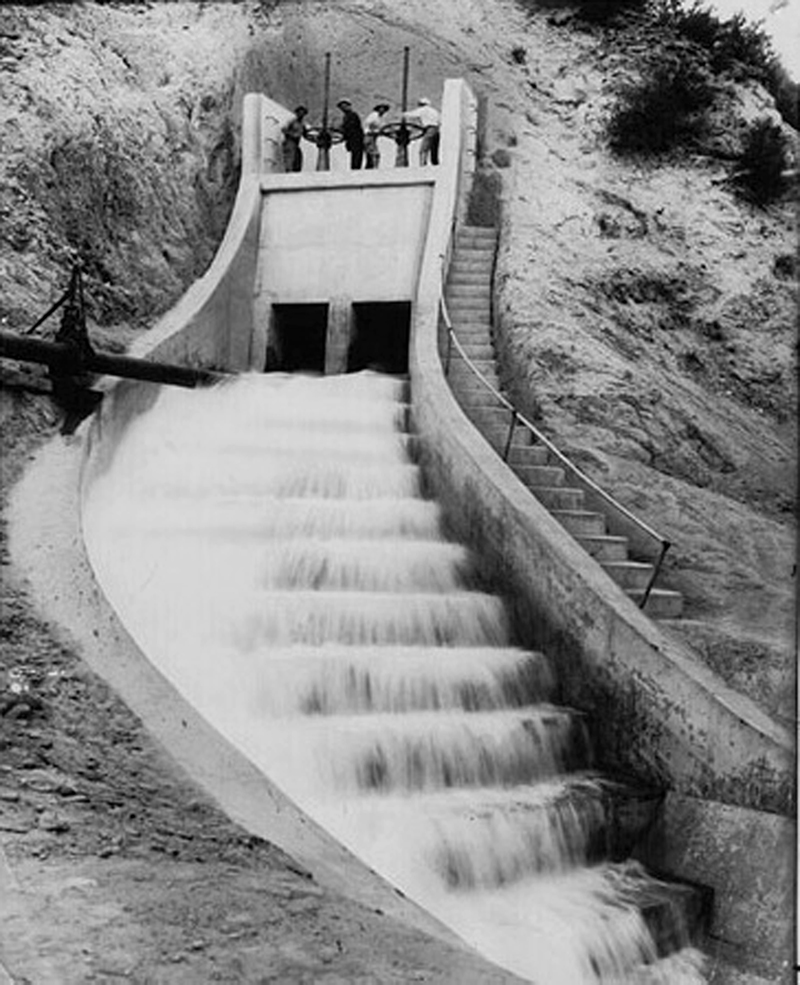

November 5, 1913: 40,000 Angelenos arrive by car, wagon, and buggy to celebrate the opening of the Los Angeles Aqueduct at the Cascades in present-day Sylmar. At the beginning of the ceremony, Mulholland rises to thank his assistants and the city of Los Angeles for their loyal support. His address to the crowd is brief: “This rude platform is an altar, and on it, we are here consecrating this water supply and dedicating the aqueduct to you and your children and your children’s children — for all time.” He pauses for a moment as if contemplating his words. Satisfied, he says abruptly, “That’s all,” and returns to his seat amid a tremendous roar from the crowd.

When the din subsides, he is recalled to bring forth the water. The good-natured but noisy crowd quiets as Mulholland unfurls the American flag at the speaker’s stand. This is the signal to Gen. Adna R. Chaffee, president of the Board of Public Works during the aqueduct period, to perform the honored task of opening the gate valves. At Chaffee’s command, five men atop the concrete gatehouse put their weight to the great wheels that will lift the gates and release the water into the canal. At the first trickle, the crowd breaks and runs to the canal. Hundreds of cups are dipped into the sparkling water. Horses rear in fright as the crowds cheer and horns blare. Next, the band plays “Yankee Doodle Dandy.”

The program called for Mulholland to turn the aqueduct over formally to Mayor J.J. Rose, who would accept it on behalf of the people. However, all semblance of order is lost. Mulholland turns to Rose, next to him on the platform, and says, “There it is, Mr. Mayor. Take it.”

1917: Construction of Powerhouse No. 1 is completed in San Francisquito Canyon.

1920: Construction of Powerhouse No. 2 is completed in San Francisquito Canyon.

1920s: L.A. sees unprecedented growth as homes and businesses spread across the Los Angeles basin.

Photo: Leon Worden.

Spring 1923: Both Los Angeles and the Owens Valley face water shortages. There were several years of subnormal snowfall in the Eastern Sierra. Meanwhile, local water use on privately owned land in the Owens Valley is increasing. Los Angeles lacks a dam and storage reservoir to control the flow of the Owens River above the aqueduct intake at Independence. The best site, Long Valley, remains in Eaton’s hands after Mulholland rejected Eaton’s asking price for the land.

To increase supply, the city begins pumping groundwater. In response to this action, farmers in the Independence area file injunctions in hopes of arresting the fall of water table levels. In Bishop and Lone Pine, residents grow alarmed at the city’s purchases of properties north of Independence for the acquisition of groundwater rights.

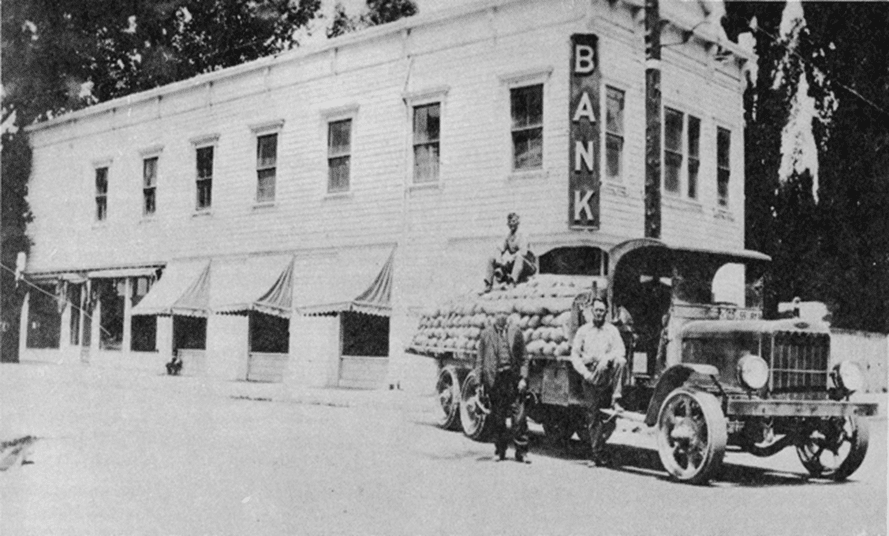

1924: The Owens Valley water wars begin. Wilfred and Mark Watterson are Inyo County’s financial leaders. As owners of the Inyo County Bank, the Wattersons organize valley residents into a unified opposition force through the formation of an irrigation district. Following the district formation, confrontations ensue and escalate.

The city purchased land and water rights indiscriminately, leading to accusations of “checkerboarding.” As a result, farmers divert water illegally, leaving the canal empty. Frustration and uncertainty prevail; area farmers feel vulnerable, unsure of the intentions of their neighbors. Therefore, more and more valley residents believe Los Angeles should buy out the entire area.

May 21, 1924: The first violence erupts. Forty men dynamite the Lone Pine aqueduct spillway gate. No arrests are made. Eventually, the two sides fight to a stalemate. Los Angeles officials believe the wholesale purchase of the district is unnecessary to meet the water demand. Instead, on Oct. 14, they hatch a plan to leave 30,000 acres in the Bishop area free of city purchases. The city also offers to promote the construction of a state highway to the area, thus creating a local tourist industry. The Wattersons and the directors of the Owens Valley Irrigation District reject the proposal, insisting on outright farm purchase and full compensation for all townspeople.

November 16, 1924: Mark Watterson leads 60 to 100 people to occupy the Alabama Gates. They close the aqueduct by opening the emergency spillway. Renewed negotiation ends the occupation.

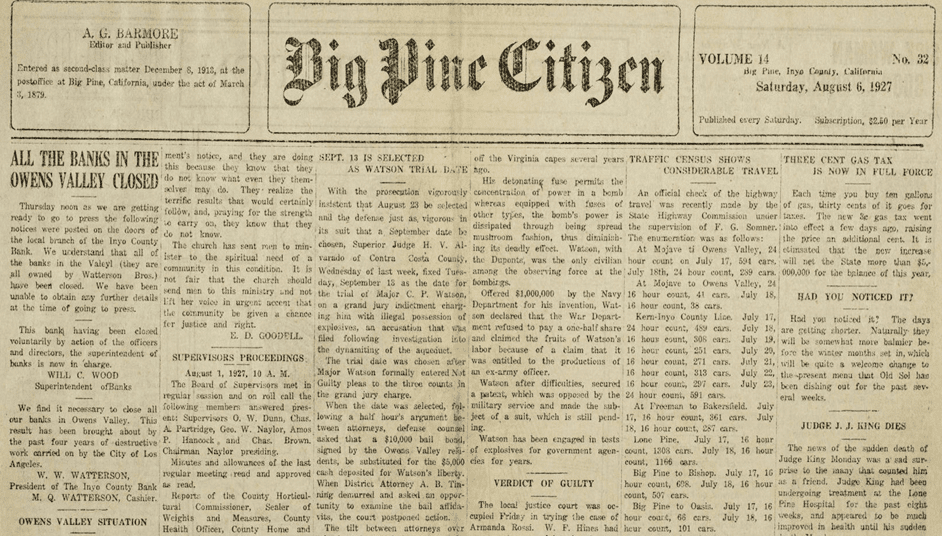

April 1926 – July 1927: Finally, the conflict is completely centered on the issues of farm purchases and reparations to the townspeople. Attacks on the aqueduct begin anew in April. By July, there have been 10 instances of dynamiting. However, just as the controversy reaches its zenith, valley resistance is suddenly undermined. The Wattersons close the doors of all branches of the Inyo County Bank. Not only are Wattersons bankrupt; they will also be tried and convicted of 36 counts of embezzlement.

1924-1926: Amid concerns about the water wars as well as earthquakes on the San Andreas Fault cutting off the aqueduct, Mulholland builds a series of reservoirs around Los Angeles to provide a reserve of water for the city.

June 1923: Preliminary studies and surveys for the St. Francis Dam and reservoir are completed. Originally, the planned site of the big new reservoir is Big Tujunga Canyon, above present-day Sunland in the northeastern San Fernando Valley. But the high values placed on the necessary ranches and private lands are, in Mulholland’s view, highway robbery. Therefore, he ceases his attempts to purchase the land.

August 1924: Construction of the St. Francis Dam begins. Originally planned to be 185 feet high, the dam is twice raised by 10 feet to a total of 205 feet without increasing the diameter of the base. Also, the dam is unwittingly built against an ancient Paleolithic landslide on its eastern abutment. Besides this, several errors are made in the construction of the foundation of the dam, except at its center section. The mixture of concrete is also of questionable quality and workmanship.

1926: Construction of the St. Francis Dam is completed.

March 1, 1926: Water begins to fill the reservoir.

March 7, 1928: The reservoir is filled to three inches below the crest of the spillway. As a consequence, Mulholland orders no more water to be turned into the St. Francis Dam.

March 12, 1928, 10:30 a.m.: While conducting his usual inspection, dam keeper Tony Harnischfeger discovers a new leak in the dam’s western abutment. Concerned about previous leaks in this same area, and the muddy content of the runoff which could indicate the water eroding the dam’s foundation, he immediately alerts Mulholland.

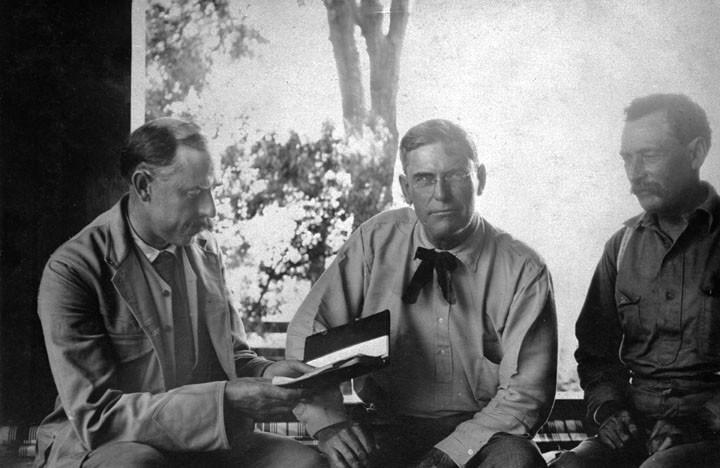

Mulholland and his assistant Harvey Van Norman arrive and begin inspecting the area of the leak. During their inspection, Van Norman discovers the source of the leak. By following its runoff, he determines that the muddy water is coming not from the leak itself, but from a place where the water contacts loosened soil from a newly cut access road. By their estimation, the leak is discharging 2 to 3 cubic feet of water per second (15 to 22 U.S. gallons). Both men observe two instances of acceleration or surging of the flow. They later testify during the coroner’s inquest that the volume being discharged was inconsistent.

Although concluding this can be done at a future date, Mulholland believes some corrective measures are needed. For the next two hours, Mulholland, Van Norman, and Harnischfeger inspect the dam and its various leaks and seepages, finding nothing of concern for a large dam of this type. Both Mulholland and Van Norman are convinced the new leak poses no threat, so they return to Los Angeles.

March 12, 1928, 11:50 p.m.: Ace Hopewell, a carpenter at Powerhouse No. 1, rides past the dam on his motorcycle. During the subsequent coroner’s inquest, he states he rode up the canyon and passed both Powerhouse No. 2 (a hydroelectric power plant) and the dam without seeing anything to cause him concern. Approximately one mile (1.6 km) upstream from the dam he hears, above the sound of his motorcycle, a noise he describes as “rocks rolling down the mountain.” He stops and dismounts from his motorcycle.

Leaving the engine idling, he smokes a cigarette while checking the hillside above him. He can still hear the sound that caught his attention earlier, although it is now fainter and behind him. Assuming it was a landslide, since they were common to the area, and satisfied he is in no danger, he continues on his way. Ace Hopewell is probably the last person to see the St. Francis Dam intact.

March 12, 1928, 11:57:30 p.m.: The St. Francis Dam collapses, beginning with a landslide of the water-saturated eastern abutment which is exacerbated by the hydraulic uplift phenomenon of the inadequately constructed base of the dam (see below). Consequently, the dam’s western abutment also fails.

The time of 11:57:30 p.m. is based on accounts by personnel of the Bureau of Water Works and Supply, both at receiving stations in Los Angeles and at Powerhouse No. 1, noting a sharp drop in voltage on their lines at that exact time.

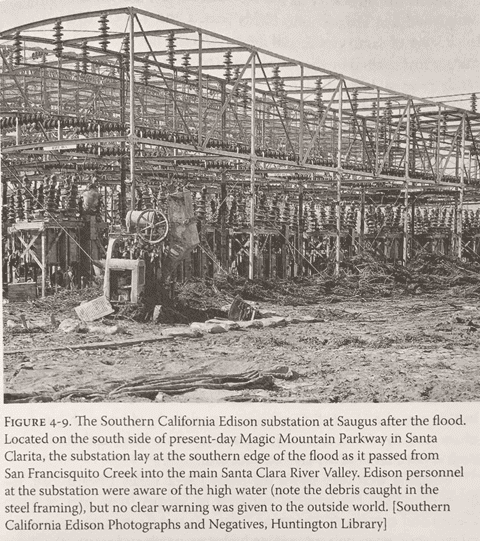

Simultaneously, a transformer at Southern California Edison’s Saugus substation (on today’s Magic Mountain Parkway) explodes. The transformer is connected to Edison’s Antelope Valley Borel power line. It runs up the western hillside of the canyon near the dam to poles located about 90 feet above the eastern abutment. Most likely, this line is severed as the eastern hillside and abutment give way. The grounded lines cause a short, which in turn causes the transformer to explode.

March 12, 1928, 11:58 p.m.: Tony Harnischfeger and his family are the first casualties caught in the 140 foot (43 m) high flood wave, which hits their cottage, approximately one-quarter mile (400 m) downstream from the dam. The body of girlfriend Leona Johnson (often mistakenly reported afterward as Harnischfeger’s wife) is found fully clothed and wedged between two blocks of concrete near the base of the dam. This leads to the notion that she and the dam keeper might have been inspecting the dam immediately before its failure. Neither Tony Harnischfeger’s body nor that of his 6-year-old son, Coder, would be recovered.

March 13, 1928, 12:03 a.m: Five minutes after the collapse, having traveled 1-1/2 miles (2.4 km) at an average speed of 18 mph (29 km/h), the now-120-foot-high (37 m) flood wave destroys the heavy concrete Powerhouse No. 2. It leaves only the two turbines and claims the lives of 64 of the 67 workmen and their family members who lived nearby.

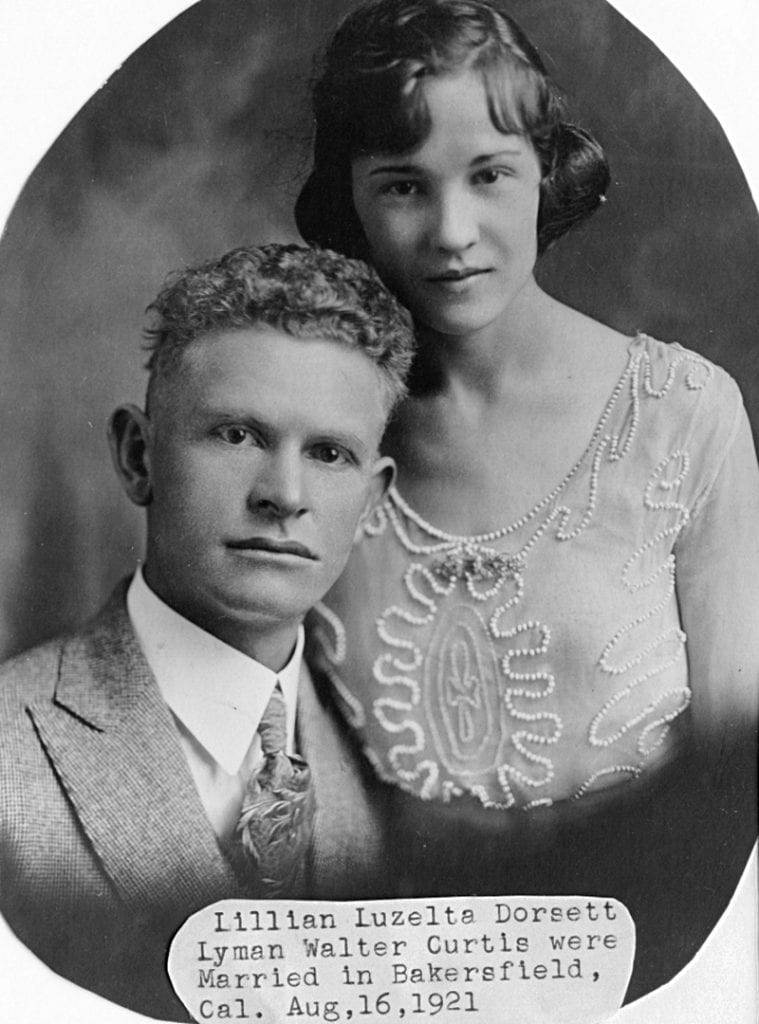

Lyman and Lillian Curtis notice a strange mist in the air and conclude the dam has collapsed. Lillian, her son Danny and the family dog head for high ground. At the same time, husband Lyman goes back into the house to gather daughters Marjorie and Mazie. Only Lillian and Danny survive.

Ray Rising, a utility man from the powerhouse, is awakened and faces a 10-story-high wall of water. Swept into the floodwaters, he manages to climb onto a floating rooftop, which transports him to safety. He is the only other survivor at this power plant.

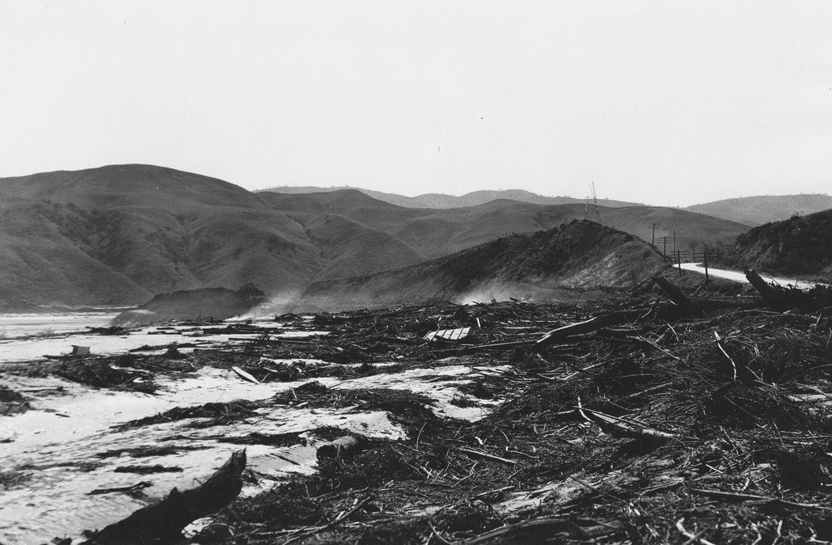

March 13, 1928, 12:05 a.m. – 1 a.m.: San Francisquito Canyon is ravaged by the flood. Six members of the Ruiz family are killed. At the base of the canyon, in present-day Tesoro del Valle, the water roars through and decimates part of actor Harry Carey’s ranch. The destruction includes a Navajo trading post, which was a popular tourist attraction at the ranch. Luckily, Carey is away on business in New York.

It was rumored that a group of Navajo Indians, hired by Carey to work at the trading post, called Carey the night before the dam ruptured and asked to leave the ranch for Arizona. Their request was allegedly based on a medicine man’s premonition of an impending collapse of the dam. However, according to Carey’s son, Harry Carey Jr., the Indians actually asked Carey for permission to leave one month before the dam break, after the medicine man went deer hunting near the dam and noticed a big crack in its face.

March 13, 1928, 1 a.m.: The deluge, now 55 feet high (17 m), empties out of San Francisquito Canyon and follows the westward course of the Santa Clara River. It partially demolishes Southern California Edison’s Saugus substation, leaving the entire Santa Clara River Valley and parts of Ventura and Oxnard without power.

At least four miles of the state’s main north-south highway (now Interstate 5) are underwater. A short distance away, near the present-day Magic Mountain amusement park, the flood is washing away the town at Castaic Junction.

Raymond Starbard, an assistant Edison Company patrolman at the Saugus substation, is nearly hit by the floodwaters. He hitches a ride to Wood’s Garage next to the Saugus Cafe. At the cafe, Starbard places a call to Sheriff’s Substation No. 6 in Newhall. Subsequently, he is credited as the first person to sound the alarm about the flood.

March 13, 1928, ~1:25 a.m.: One hundred fifty Edison Company linemen are asleep in their tents at Kemp, a temporary camp near a railroad siding just east of the Los Angeles-Ventura county line. Nightwatchman Ed Locke watches in horror as a huge flood of water approaches the camp at 12 mph (19 km/h). Locke runs through the camp, waking as many people as possible.

The water hits a geological outcropping called Blue Cut and doubles back on the camp, creating a whirlpool that uproots the tents. Most of the workers who survive had buttoned up their tents, allowing them to float on the whirlpool. Eighty-four of their fellow workers perish on this night, along with Locke — a true hero of the disaster.

March 13, 1928, 1:30 a.m.: Telephone operators such as Louise Gipe in Santa Paula and Reicel Jones in Saticoy — subsequently nicknamed the “Hello Girls” — bravely stay at their posts and begin systematically calling residents in low-lying areas. They urge them to flee to higher ground. Gipe is at her station when, shortly before 1:30 a.m., she receives a message from the chief operator of the Pacific Long Distance Telephone Co. saying the St. Francis Dam has broken. They warn her that a tremendous wall of water is sweeping down the valley. She receives orders to notify the authorities and then warn those in the path of the flood.

Gipe immediately calls California Highway Patrol officer and Santa Paula resident Thornton Edwards with the news of the flood. She then starts calling the homes of those in danger. Edwards is soon joined by another officer, Stanley Baker. The two men use their motorcycles to awaken and warn residents by leaving their sirens running and crisscrossing the streets in the danger zone. Whenever a resident comes out to investigate the commotion, the officers stop, give orders to evacuate, and instruct the citizen to pass along the warning.

Edwards and the Baker ride for more than an hour through the lower sections of Santa Paula. Initially crowded with people, the streets are now mostly empty. Little more can be done in Santa Paula, although ranches and dairies in lowlands west of town might not have gotten the message. Edwards and Baker cover all territory accessible by motorcycle and warn those who have not received a telephone call.

Taking different routes, the two head back to town. Sirens scream alarms sound and many residents are saved as they rush to the hills only to watch their homes get crushed below them. For his wild yet courageous ride, Edwards is remembered as the Paul Revere of Santa Paula. In 2003 a statue was erected in Santa Paula in Edwards’ and Baker’s honor.

March 13, 1928, 2:30 a.m.: The phone rings at the Mulholland residence. The Chief’s daughter answers and wakes her father with the terrible news. As he lurches for the phone, he repeats the mantra over and over: “Please, God, don’t let people be killed. Please, God, don’t let people be killed.”

Mullholland issued the following statement: “I would not venture at this time to express a positive opinion as to the cause of the St. Francis Dam disaster. … Mr. Van Norman and I arrived at the scene of the break around 2:30 a.m. this morning. We saw at once that the dam was completely out and that the torrential flood of water from the reservoir had left an appalling record of death and destruction in the valley below.”

March 13, 1928, 5:30 am: Having devastated much of Santa Paula and heavily damaging the towns of Fillmore and Bardsdale, the floodwaters empty into the Pacific Ocean near Ventura at Montalvo, washing victims, and debris out to sea. It took 5 hours and 27 minutes to travel 54 miles (87 km) from the dam site to the ocean. As it reaches the coast, the flood is nearly two miles wide (3 km), traveling at 6 mph (9.7 km/h). Bodies of victims are recovered from the Pacific Ocean, while others are never found.

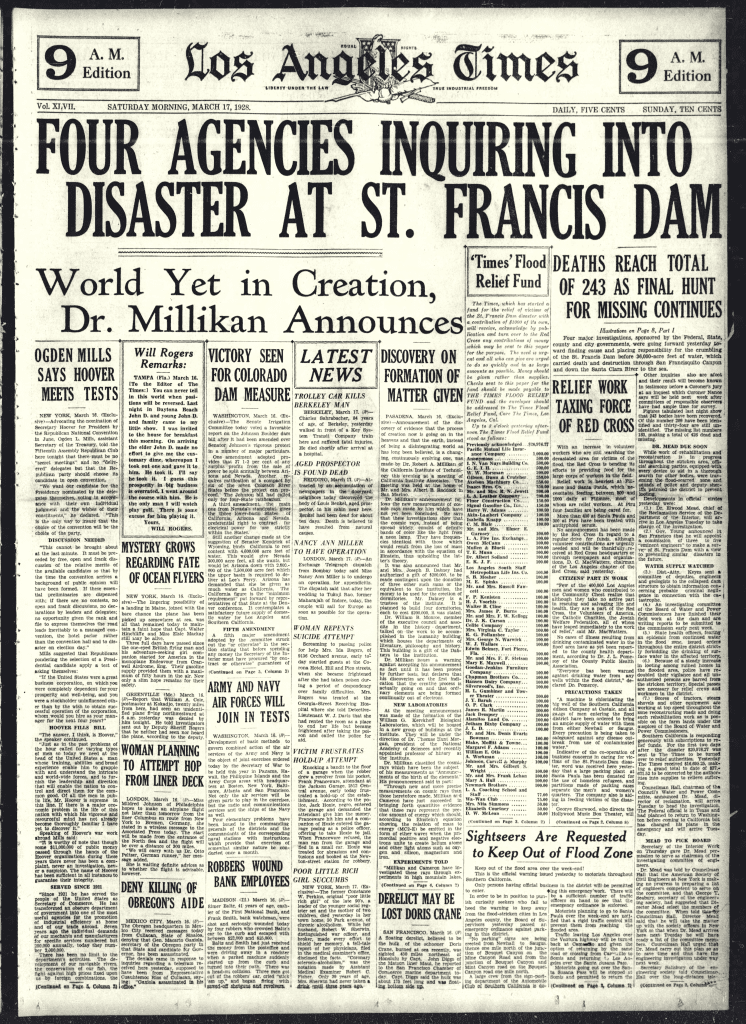

March 17, 1928: The Los Angeles Times headline screams: “FOUR AGENCIES INQUIRING INTO DISASTER AT ST. FRANCIS DAM.” Immediately following the dam break, as many as eight agencies — city, county, state, and federal — begin investigating the cause of the disaster.

Most significant is the two-week coroner’s inquest led by the ambitious Los Angeles District Attorney Asa Keyes. Keyes and the coroner’s jury relentlessly question Mulholland about the composition of the concrete, the selection of the dam site on an earthquake fault, the construction and drainage of the dam’s foundation, the anchoring of the dam to the walls of the canyon, and Mulholland’s unquestioned role in supervising the dam construction. Keyes accuses Mulholland of ignoring reported leaks in the dam, days before the failure.

Asked by Keyes if he would build the dam on the same spot again, Mulholland replies: “No, I must be frank and say that now I would not.” Keyes presses on, asking Mulholland why not. The reply: “It failed, that’s why. There is a hoodoo on it. … It is vulnerable against human aggression, and I would not build it there.” Mulholland suspected the dam was dynamited by an Owens Valley conspiracy ring to avenge its construction. Toward the end of his testimony, Mulholland humbly states: “Don’t blame anybody else, you just fasten it on me. If there is an error of human judgment, I was the human.”

After the inquest, the coroner’s jury finds: “The destruction of this dam was caused by the failure of the rock formations upon which it was built, and not by any error in the design of the dam itself or defect in the materials on which the dam was constructed.”

Although jurors express ambivalence about the inciting event leading to the collapse, they feel the preponderance of evidence favors an initial failure on the dam’s western abutment, which was anchored to a rock called red Sespe conglomerate. During the inquest, Keyes demonstrates how this rock disintegrates when exposed to water.

Jurors place the blame squarely on the shoulders of Mulholland and his Bureau of Water Works and Supply. They further attack the unquestioning trust in Mulholland’s expertise. The final jury statement makes national headlines: “The construction of a municipal dam should never be left to the sole judgment of one man, no matter how eminent.”

March 1929: Mulholland takes full responsibility for the worst U.S. civil engineering failure of the 20th century and resigns from his office. During the coroner’s inquest, he had said, “The only people I envy in this whole thing are the dead.”

August 14, 1929: The Department of Public Works, under the administrative oversight of the State Engineer — later assumed by the Division of Safety of Dams — is authorized to review all non-federal dams over 25 feet high or which would hold more than 50 acre-feet of water (1 acre-foot of water is 325,851 gallons). The new legislation allows the state to employ consultants as necessary, and the state has full authority to supervise the maintenance and operation of non-federal dams.

March 12, 1934: Eaton dies — coincidentally, on the sixth anniversary of the dam failure. In the end, Eaton’s desire to enrich himself from the sale of his land in Long Valley drives a wedge between himself and Mulholland. They break off all contact when Eaton asks for $1 million for the land which Mulholland needs for a storage reservoir dam. Mulholland considers Eaton’s demand extortion. The deadlock ultimately destroys both men. While holding out to sell the dam site at his price, Eaton’s finances crumble. In 1928 they collapse altogether with the failure of the Owens Bank.

July 22, 1935: Mulholland dies in his home. His assistant, Harvey Van Norman, succeeded him as chief engineer and general manager upon Mulholland’s retirement. Mulholland was retained as Chief Consulting Engineer with an office, receiving a salary of $500 a month.

In later years, he goes into self-imposed semi-isolation. Shortly before his death at age 79, he consults on the Hoover Dam and Colorado River Aqueduct projects.

In Los Angeles, where transgressions are quickly forgotten and celluloid heroes are made, Mulholland is revered as the superstar who brought L.A. the water it needed to grow into a major, world-class metropolis. The Mulholland Dam in the Hollywood Hills, Mulholland Drive, Mulholland Highway, and the William Mulholland Memorial Fountain at Los Feliz are named in his honor.

1963: Charles Outland, in has landmark 1963 book, “Man-Made Disaster: The Story of St. Francis Dam,” concludes that Mulholland bears the brunt of the blame for the disaster.

1974: A fictionalized story based on the California water wars is the basis of the 1974 Roman Polanski film, “Chinatown.” The character of Hollis I. Mulwray appears to be drawn from Mulholland.

1992 and 1995: In his published papers, Dr. J. David Rogers, Chair of Geological Engineering at the University of Missouri-Rolla, determines the failure actually started on the eastern abutment where the dam — unbeknownst to Mulholland and his engineers — was anchored to an ancient Paleolithic landslide made up of the rock Pelona schist. As the dam was filled between 1926 and 1928, this unstable hillside became saturated with water, causing a massive landslide on the evening of March 12, 1928. It was just five days after the dam had been filled to near capacity for the first time on March 7.

Rogers also notes the failure to widen the base of the dam when its height was twice raised by 10 feet beyond specifications to increase its storage capacity. He shows that, due to various deficiencies in the construction of the base of the dam, the collapse caused the structure to be lifted by the force of the water and tilted downstream in a phenomenon called hydraulic uplift.

Rogers notes that the famous center section of the dam, or “tombstone,” which remained standing, was the only portion of the dam built correctly with 10 uplift relief walls at the base. The landslide caused the entire eastern part of the dam to collapse first, with large blocks of the shattered portion of the dam carried across the downstream face of the main dam. The center section of the dam was then undercut, tilting and rotating toward the western abutment, resulting in the collapse of the western portion of the dam.

2004: Donald C. Jackson, Associate Professor of History at Lafayette College, Easton, Penn., and Norris Hundley Jr., Professor of American History at the University of California, Los Angeles, published an article in the California History journal titled “Privilege and Responsibility: William Mulholland and the St. Francis Dam Disaster.” Now the blame shifts back to Mulholland.

Jackson and Hundley point out that while Mulholland correctly placed drainage wells at the base of the dam’s center section, he chose to forgo this and other necessary procedures on the outer parts of the dam. They claim he ignored the possibility of the uplift phenomenon in those sections as water seeped into the adjacent hillsides.

The authors note that, before 1910, little attention was paid to hydraulic uplift in dam building. However, concerns about the phenomenon were expressed in the late 1800s and intensified with the collapse of a concrete gravity dam in Austin, Penn., on Sept. 30, 1911, with the loss of at least 78 lives. The cause was identified as hydraulic uplift.

With this tragedy in mind, several curved concrete gravity dams were built across the country during the 1910s and early 1920s — all before the St. Francis — with protections against the uplift problem that included extensive grouting, placement of a drainage system along the length of the dam, and a deep cut-off trench.

At least three technical books published in the 1910s discussed the dangers of uplift and how to compensate for it. Jackson and Hundley further claim: “By 1916-1917, serious concern about uplift on the part of American dam engineers was neither obscure nor unusual. Equally to the point, in the early 1920s, Mulholland’s placement of drainage wells only in the center section of St. Francis Dam did not reflect standard practice in California for large concrete gravity dams.”

The authors conclude: “Despite equivocations, denial of dangers that he knew — or reasonably should have known — existed, pretense to scientific knowledge regarding gravity dam technology that he possessed neither through experience nor education and invocations of ‘hoodoos,’ William Mulholland understood the great privilege that had been afforded him to build the St. Francis Dam where and how he chose. Because of this privilege — and the decisions that he made — William Mulholland bears responsibility for the St. Francis Dam Disaster.”

October 2011: Initiation of the Forgotten Casualties Project, a multi-year study under the direction of archaeology Professor James Snead of California State University, Northridge. The primary goal of Snead and his team of CSUN anthropology graduate and undergraduate students is to humanize the tragedy by discovering the identities of each of the victims and telling their stories.

February 2014: Publication of the first-ever comprehensive list of dam victims, compiled by Ann C. Stansell, a California State University at Northridge graduate student in anthropology/public archaeology, as a component of the Forgotten Casualties Project.

August 2014: Publication of the aforementioned Ann C. Stansell’s master’s thesis, Memorialization and Memory of Southern California’s St. Francis Dam Disaster of 1928.

Noting that the disaster has been “forgotten on a state and national level, but (is) tenuously remembered within the flood zone,” the work “synthesizes archival and survey data to better understand how the disaster and the dead have been commemorated throughout the 54-mile flood zone: spatially, through state monuments, community memorials, grave markers, and memorabilia, and conceptually, through poems, songs, and oral histories.”

In a broader context, it seeks to identify “what parts of the past are remembered, and how they are remembered and interpreted,” to understand the development of collective memory and explore how legends and traditions are established.

Some of the information in this chronology was adapted from the website of the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power and here: http://wsoweb.ladwp.com/Aqueduct/historyoflaa/index.htm (no longer an active link).

Dr. Alan Pollack is President of the Santa Clarita Valley Historical Society and President of the St. Francis Dam National Memorial Foundation.

Estimated reading time: 30 minutes